11,342 words / 1:08:49

Buttercup Dew has produced a new version of this film with much improved video and images, but with the same narration by Bowden. The original version produced by Bowden in 2008 is beneath it.

* * *

* * *

Editor’s Note: The following transcription was made by V. S., with additions and notes by Buttercup Dew. Where public domain images of the works described by Bowden are unavailable, we have included links to offsite images of them.

Welcome to this brief film about English and British sculpture.

Stonehenge

Let’s begin right at the beginning with something which can’t really entirely be described as a sculpture, but it’s Stonehenge, an enormous and a sort of semi-celestial monument the better part of 4,000 years old.

Grim, chthonian, profound, a pagan cathedral, freestanding. The Christianity of 2,000 years left it alone, and in a strange way the English and British monumental tradition in stone begins with this piece. There’s an extraordinary leap as well across the better part of four millennia to modernist sculpture which, Henry Moore-like, epitomizes the primitive and the fierce and the primeval and even the tribal.

So, let’s begin this analysis of what we have done three-dimensionally in the arts with the first cathedral that has come down to us on these islands from the ancient world.

The Torrs Chamfrein

Here we move on in time to a Celtic horse-mask[1] from southern Scotland circa 200 BC or thereabouts, slightly dented now as it comes down to us, pre-Germanic in feel, ancient Celtic. The symbolism of snakes, almost, and swirls and that patterning that Celtic art so beloves. Obviously, it’s an item that comes from the battlefield and is essentially a piece of armor to protect a horse or to signify the power of a horse. In it we see something of pre-Germanic Britain, of a Britain that is yet to be influenced by Romans or people of Germanic ancestry, a Britishness that is differentiated in terms of how we perceive it the better part of 2,000 years on.

Many of these items, small and large, particularly coins, have come down to us, often elongated, often with slightly surreal shapes. Celtic craftsmen weren’t interested in realism, and their art was essentially not abstract but mystagogic and followed from the nature of their legends and their myths.

The Gorgon on the pediment of the Temple of Sulis Minerva

Here we move forward to the influence of the Roman civilization on the British Isles. This is a particularly British interpretation of a Classical legend. It’s the head of a medusa,[2] the snakes as hair swirling around the actual physiognomy of the piece. Yet this piece is not really Italianate. It’s not that Classical in feel. It’s very British and even English. It was found in Bath in the West Country, and it comes to look, to my mind, as a sort of heavy piece: solemn, fiercely etched, non-Classical in its lineaments, a sort of transliteration of Romanesque art into British terms. We’ve taken their material and interpreted it in accordance with our craftsmen, and you can leap forward almost to the images on the outside of steeples in the Middle Ages from this type of art. Fierce, slightly primitive: You can almost sense an Italian of the era would wince. But we’ve taken it into ourselves and made something different out of it.

The head of Antenociticus

Here we have something in the same era, a British variation on a Roman theme. Two images for the price of one, one of them extraordinarily modernist looking. The one on the left, as you look at it, could almost be a piece by Elizabeth Frink, say, from the middle of the twentieth century. But again, these are British takes on Roman ideas about their gods, one from Gloucester and the other from Northumberland.[3] One thing you will notice about them is their heaviness, their three-dimensionality, their earthy solidity. There’s a certain absence of Classical lightness, but there’s an ur-primeval and deeper consciousness, a more Northwestern European consciousness, not a Southern European one. Again, we’ve taken Roman cultural archetypes, motifs, and forms into ourselves, and our craftsmen have obeyed their Roman masters, but in a sense they have produced something which is irredeemably British.

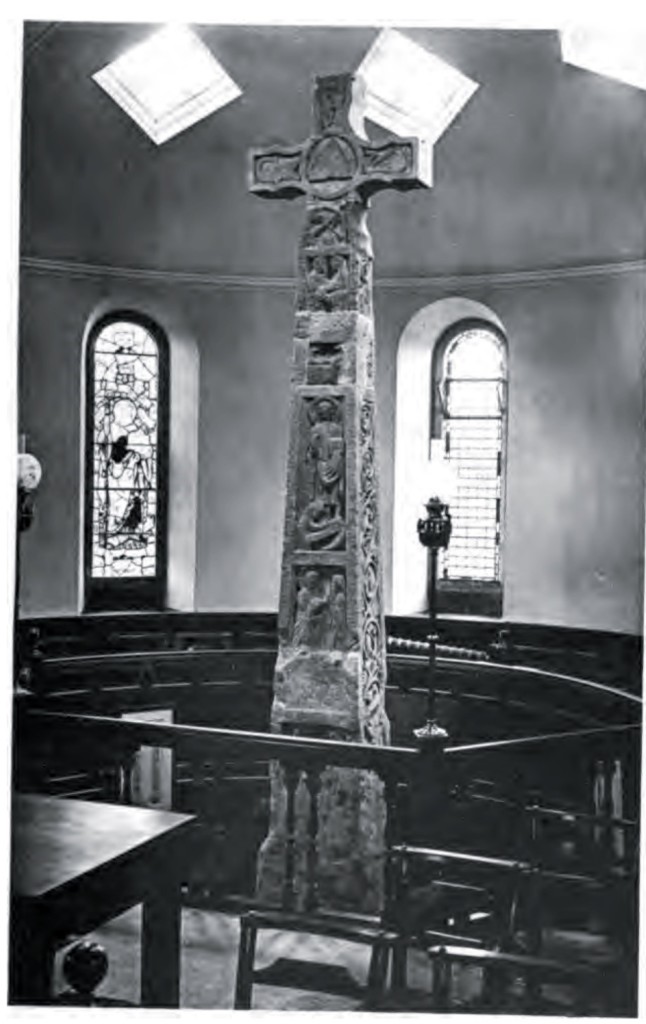

The Ruthwell Cross

Here we have a Northumbrian Christian cross,[4] leaping nine centuries forward from the last exhibit. Very Christian, slightly Romanesque, smallish figures outlined in semi-relief against the texture of the cross as it goes up. To my mind, there still seems to be certain pre-Christian iconographic elements to the piece. The thing that strikes me, though, is that differentiated from the Celtic art that we looked at before, but very much in spirit with the more Roman art that we evaluated a moment previous to this, there’s a solidity to the piece — a strength, an insularity, and a grandeur which goes through all British three-dimensional art whether Celtic, Romanesque, Christian, explicitly pagan, Restorationist, modernistic. This sense not of heaviness, but of the gentility of strength and of a sort of residential power to three-dimensional space.

The “Romsey Christ”

Here, moving on in time, we sense a Saxon and an explicitly Germanic influence in Christian English art, as we can now call it. The sculpture is still embedded on a wall, on a plane.[5] It’s partly relief, but as you can see from its three-dimensionality, the figure of the crucified Christ wants to come out of the wall and is almost, one could say 50%, three-dimensional. It’s not going to take too much for it to burst out of the wall, off the cross, and be a configured figure in its own right. Again, we see not just a Christian influence ideologically and theologically, but that element of profundity and heaviness and truth to materials and prior solidity which I believe is a quintessential part of English and British three-dimensional form. It’s interesting that these things remain extant no matter the change in historical period or the overlying culture. We pass from a primeval paganism to a Celtic influence to an influence of imperial Rome to an influence of early Middle Ages Christianity, and yet some of the abiding ethnic themes that lie behind the delineation of three-dimensional art remain the same.

Tomb effigy of Queen Eleanor of Castile

Here we move slightly forward in time to an extraordinary image which could be said to be the beginning of the high-art sculptural tradition in England as it has come down to us, as it will be interpreted by critics like Orpen[6] in the early part of the twentieth century just gone. This dates from 1290 and is an effigy[7] made by William Torell. One of his first ones, a life-size bronze — it’s an extraordinary piece. Imagine that it’s incredibly heavy, highly wrought, the full length of a man’s course, metallic, powerful. But again, you have amidst the finery and appurtenances of the form a strength, a physical power, a solidity even in repose. Ideologically, it’s supposed to show the redemption of a Christian and knightly grace in death. But I think it very much relates, too, in its three-dimensionality many of the images that we’ve seen before. So powerful even in its metallic form that it survived the better part of a thousand years and will probably be extant a thousand years from now. This is the bringing together of stoicism in form, grace, solidity as to material, truth to materials (to use a modern slogan), and the quiet power of the English three-dimensional tradition.

Here we have an image in bronze again, highly weathered, of Richard II,[8] the subject of a Shakespeare play. Again, very much seen in a Christian vogue, a Christian knightly monarch looking slightly meek and humble, how you were supposed to look in the era. Very strongly three-dimensional; good line; powerful, squat nature of the features and upper shoulders. He’s depicted slightly as an apostle. But again, these are part of the conventions of the period. But again we return to this theme of compactness, stoicism, truth to material, and solidity. In all of English and, to a slightly lesser extent, British sculpture there is this deep, quiet, and reverberating sense of power in the depiction of the face, the upper body, or the entire frame.

Christ’s resurrection, fourteenth century Nottingham Alabaster [4]

Here we have an image from the fourteenth century from Cambridgeshire[9] from a provincial church. It strikes me as a very Germanic image, this one. Almost completely three-dimensional, but with a certain element of relief. But the relief becomes ever more studied, ever more withdrawn. The figures are bursting through into three-dimensionality. This is a scene of the ascent of the Christ after death, after the resurrection. He appears both as a victim and as a monarch, or celestial king. The Roman soldiers — who actually look like Medieval warriors of the time because those are the forms or archetypes upon which the anonymous sculptor is drawing — fall back in amazement and consternation before this risen being, who’s almost sort of walking out of the relief to what is perceived to be a semblance of glory.

Julius Caesar, sixteenth-century terracotta roundel [5]

Here we have a terracotta from the 1540s. It doesn’t really relate to pure English art that much, but what we see here is an opening out in the Tudor period to continental influence. So, we’re dealing with a sort of re-Europeanization, or a return of the sculpture of the ancient world in the form of a bust relating to Julius Caesar.[10] But it’s the opening to intellectual ideas on the continent. And although you could say that in the Middle Ages we internalized lots of continental ideas, here are Italian sculptors coming over at the behest of the court structures of the day to bring High Renaissance material within the purview of the English tradition. And from now on we see a mixing of what existed before and the high art of the Renaissance coming over to Britain and England in order to curry its trade. We see a sort of fusion of various European styles as the whole of the European civilization is beginning to wean itself away from the Middle Ages, and it’s beginning to look towards the creation of Early Modern Europe. You have this sensibility which grows up during this century and the one to come after it which involves a gradual de-Christianization, a return of the Classical in various dimensions — this is the classicism of the ancient world — and a slight mobility and a loosening of the rigid forms of Medieval and post-Medieval art.

Kings College Chapel, Screen with Face

Here we have another example of the High Renaissance.[11] It’s the lightish spirit of Michelangelo come over to England, hopped over, and in wood. It’s from King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, forcing house and academic stamping ground of the upper-class elite of the time, of course. Again, it’s the belief in all things Italian and Renaissance in spirit and style in stone, in bronze, in wood, in jewelry, in literature, and elsewhere. So, we’re taking during this period whole handfuls of Renaissance sensibility from the southern part of Europe and bringing it across and internalizing it as part of the national tradition. Now, what’s really happening here is two things: We’re opening up to a humanism which is European, we’re opening up to certain post-Christian sensibilities, and yet at the same time we’re going back to certain of the conceits and styles of the ancient world. But we don’t know entirely what they were, so we are stylizing what we imagine the ancient craftsmen did in bas relief, in two dimensions, in three dimensions, and we’re bringing it forward several thousand years as Christianity begins to loosen its hold on the European imagination and we connect via Southern Europe and its cultural influences with the Classical world.

The Wriothesly Family Monument [6]

Here we see a major sculpture from 1592 by Gerard Johnson the Elder. The tradition is well advanced now. This sculpture deals with death, of course, and an enormous amount of monumental masonry and three-dimensional sculpture deals with the relief of death both inside and outside Christianity. The power and solemnity of the tomb or mausoleum, the desire to incarnate oneself as a living corpse after death, the power of a provincial noble family to be seen for the entire community possibly for hundreds of years. This is the Southampton tomb at Titchfield.[12] And yet it’s also of a very important patron in the history of English art. This is the Third Earl of Southampton, who was Shakespeare’s patron.[13] The arts in all eras have to obtain money because they can’t finance themselves in a completely freestanding way. In this era, aristocrats and very rich individuals from the upper class would give money and be seen to give money to the arts as part of an organic tradition. But they always had a certain element of self-interest and they always wanted their family, such as through the vehicle of a tomb like this, to be the recipients of their largesse. So, the money is given. An enormous tomb of massive monumentality is built to a local dignitary. And you can sense the power in this church. Not only is it very big, very tall, very solid. There are these spear-like menhirs on the four corners of the tomb that make these stone corpses in state look like images from ancient Egypt, almost. It’s a sort of grandiloquence and power of an aristocracy that had life-and-death powers over the rest of society, brooked no word against them, and were totally in charge. It’s also the sign of a ruling group that is completely self-confident in this world and what they presume will be the next.

The West Face of the Great Fire of London Monument [7]

This is another piece, a relief but yearning and striving in its stone-like quality for three-dimensionality. This is by a grave sculptor, Caius Gabriel Cibber, a Dane, who did an enormous amount of work during this Baroque, Augustine, and allegorical period. This is a truly sort of eighteenth-century version of a Classical conceit as they attempt to realize it. Charles II pleads on behalf of art and science and the muses to restore a damaged London which has been ravaged by fire and destruction.[14] It’s a sort of heroic, post-Renaissance painting in stone. Everyone’s highly idealized, everyone’s outward-looking, everyone’s made to look as noble as possible. Cibber, in turn, was an extraordinary sculptor, who’s quite famous now for influencing some modernist sculptors, because two of his most famous pieces are the grotesque and gibbering figures outside of what used to be Bedlam Hospital in South London. One’s called Melancholy and the other is called Raving Madness. They’re interesting grotesques that partly relate to Medieval art and now are still there outside the entrance to the Imperial War Museum[15].

The West Pediment of St. Paul’s Cathedral [8]

Parian Ware Bust of Princess Victoria of Kent

Here we have a relief, again very solid in its two-to-three-dimensionality, from St. Paul’s Cathedral. It shows a Biblical scene, the conversion of St. Paul or Saul, who sees the divine light. On the road to Damascus he’s thrown from his horse, and the persecutor of the Christians becomes the founder of Christ’s Church. And yet in a strange way, to my mind, the Baroque or post-Baroque and highly individualized sensibility of the piece doesn’t have that much to do with Christianity. It’s a typically post-Renaissance work whereby Christian discourse and narrative and heritage is used as the model on which you do a modern version of a Classical sculpture. So, we’ve got the horsemen rearing up [and] being thrown from their mounts, the divine Sun coming down from the clouds, and all of these Israelites, as it were, are depicted like warriors from the ancient world who are mysteriously wearing armor and carrying weapons that are from the beginning of the eighteenth century. This dates from 1706, and it’s by Francis Bird, who’s a very famous sculptor of the period, [and] who did an enormous amount of work in and around St. Paul’s. Probably the modern sensibility would find his version of the Duke of Newcastle in that cathedral to be the most interesting of his works. This is a savage and rather grotesque piece in the form of a large sculptural tomb in which two skeletons tear apart the bottom end of an oak tree.

Here we move forward a little bit in time, but the vogue in the sensibility is still very much the same. This, believe it or not, is a bust of the then Princess, and later Queen Victoria. It’s from the collection at Windsor Castle and dates from 1829, by William Behnes.[16] You notice the young Victoria is depicted much like the present Queen’s [Elizabeth II] painting by [Pietro] Annigoni as a sort of exultant and superbly modeled being, and she looks like the young daughter of a Roman Senator. But this is very much the way in which the English and British nobility wished to be perceived at that time: a certain sort of yearning and sort of expectant and transcendent quality. These busts were done for almost anyone of renown at the time, and they would have been done in her case by Royal commission and for such patronage.

Although we’ve leapt from the beginning of the 1700s to the early section of the century that follows, you notice that this type of work is all of a piece and there is a contiguous nature to English and British sculpture between the Restoration in 1660 and, say, the Great Reform Bill in 1867. You can virtually say the sensibility that masters the sculpture of this period straddling over a century and a half is the same sensibility. It’s pre-Romantic, it’s Augustin, it’s highly classical, and it’s a light, stylized early Michelangelo-driven interpretation of what the sculpture of the ancient world would have been like. There are many, of course, falsities and discontinuities because ancient sculpture was highly decorative and painted. We see it without paint, because all the paint has rotted off. We see it as white stone or, on occasion, marble, but in actual fact when these images are recreated, as they have been in the twentieth century by imagization techniques, particularly pioneered by the Victoria and Albert Museum, we get a totally different idea of what ancient sculpture was. So, this is our idea of unpainted ancient sculpture thousands of years on in order to celebrate the then imperial British aristocracy.

Lady Rachel Fane (1613-1680) [9]

And here we have another piece of stylized and slightly Baroque classicism, although more stereotypically Classical in its way. It’s of an aristocrat, the Countess of Bath,[17] and it’s by Balthasar Burman. Again, it’s this attempt to heroicize, through the revisualization of the ancient world, the aristocracy from the seventeenth, the eighteenth, and eventually the first half of the nineteenth century. So, you have this sensibility which you will see in churchyards and vicarages and churches in particular up and down the country whereby the nobility identifies themselves with the Christian tradition, with the Classical tradition, the Greco-Roman and Hellenistic tradition, and wants to celebrate through patronage their power and solidity in stone.

Sir John Thornycroft (1613-1680) 1725 [10]

Here is another piece[18] that relates to the style that I’ve just described. It, again, is of a provincial aristocrat or, at the very least, an august figure: Sir John Thornycroft. Whether he relates to Tory politicians with that name in the twentieth century, I’ve got no idea. This is by Andreas Carpentier. If you notice, the way in which this individual wants to be depicted, he looks as though he’s a drunk associate of a poet like Catullus in ancient Rome where he’s lying on a bed or on the floor of a party, making an allegedly witty remark, wearing a toga and an eighteenth-century wig! So, you see that people in vogue in their century wanted to be depicted as the heroes of the ancient world, particularly in literature and in the arts. So, it’s partly a fantasy that these people had about themselves, but it’s also part of the power of the West.

In the middle of the twentieth century, a rather dissident American figure called Lawrence R. Brown, who was an engineer, wrote a book called The Might of the West, and these people believed totally in the Western civilization and they believed in its domination and they believed in its civilizing mission. They believed it extended through from various incarnations in the ancient world. These were people who had no doubts about themselves, about their society, its extension imperially across the Earth, and the power of their own nationalities. They also saw themselves, Christian or otherwise, as the inheritors of the Classical tradition. Full stop.

Lady Frederica Stanhope (1800-1823), 1825 [11]

. . . in Augustin vogue. It’s Lady Frederica Stanhope from Chevening in Kent, 1825.[19] Slightly daring here, because she’s actually feeding her young child, lying on her side in repose, although of course the sculpture is a tomb and is meant to imply death. But maternal expressions of any sentiments involving female sexuality would be permitted in this period. Don’t forget we are slightly before what will become the High Victorian period. We have unnecessarily restrictive views about this time. We think this period was incredibly prudish and so on, when if you looked at its three-dimensional art, you wouldn’t actually draw that conclusion. The reason for this is the classicizing and Hellenistic tendencies which are so pronounced, so naked — almost literally so in this case. This sculpture is by Sir Francis Chantrey, and it, again, is part of this idealizing tendency in the aristocracy of the day to see themselves as the British equivalents of the leaders of the Roman Empire.

Bust of George III [12]

Here we have a bust, a sculpture from the same era.[20] It’s in Burlington House, which is in Piccadilly, right in the center of London, and which today is the center of the Royal Academy. Although technically private, you could regard the Academy as the leading state art institution, the National Gallery excepted, in Britain. The piece is of George III, dates from the 1770s, and is by an Italian artist and sculptor, Agostino Carlini. In the sort of somber magnificence of this truculent German who wants to be seen as a sort of Augustus, really, a sort of modern Roman Emperor. Wearing a toga, of course, which people in his era didn’t really wear. Looking solemn, looking fierce, looking statesmanlike, if rather sober-minded and sort of lugubrious. No signs of the putative insanity which would have him leaving the coach in Windsor Great Park and engaging in excited conversation with the oak trees.

William Wilberforce by Samuel Joseph, 1840 [13]

Yes, here we have a major monumental piece of sculpture: life-size, very biographical, very characterful. The classicizing and heroicizing elements are downplayed, and we have a certain representational portraiture in stone and, of course, in three dimensions. This is in Westminster Abbey, and it’s of the reformer and anti-slave trader William Wilberforce. Now, this piece, which is very characterful — and you can sense the liberal-minded Whiggish sentiments and sensibility of this very upper-class gentleman of his era, influenced by humanism, Enlightenment, and post-Renaissance ideas as well as the dawning of the high liberalism of the middle Victorian period, as well as extremely Christian sensibilities. Nevertheless, there are different ways of looking at Wilberforce, because many slave-owners of the time wanted to introduce a mass class of black slaves beneath the white proletariat in Britain. So, paradoxically, and in a rather revisionist vogue, it is possible to see Wilberforce as a man who may not have wanted this, but he did preempt the creation of explicit multiracialism in Britain by maybe 120 odd years before it actually began to get underway in the middle of the twentieth century.

Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster with Cupid and a Putto, 1790 [14]

Here we have very much a Classical image from the same period, the late 1700s: Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster with Cupid and a Putto by John Deare.[21] An aristocrat[22] would have commissioned this. We see her stroking the head of a horse, a rather serpentine-looking horse. Again, quite an erotic piece, a nude. You’re a philistine if you’re against it. A very important point here: In nearly all Indo-European or Aryan art, there’s a strong concentration on the body and on the physicality of the body and the sexual delineation of the body, it has to be said, particularly in three dimensions. This is very much the pre-Christian tradition of the Hellenes and of the ancient world. This corporeal element, this purely bodily and physical element, is at the core of Western art and Western sensibility in complete contravention to the Islamic civilization, for instance, which completely disprivileges the depiction of the face, the hands, the body, and believes that all corporeal images, whether the three- or two-dimensional, are non-transcendental and erotic and therefore are forbidden. Extreme forms of Orthodox Judaism, which disprivilege art, are the same. You see in this tradition a very strong element of core Western art — strong enough even to resist some of the critical and censorious blandishments of Protestant Christianity.

Two Sleeping Dogs, 1784

Yes, this is a slightly sentimental piece in mock Classical vogue. It’s by a female sculptress, Anne Seymour Damer. It’s of the dogs. It’s very Victorian in sentiment, if you like. It’s a sentimental piece about two dogs. There’s nothing really much more to say about it than that. It does relate to the sort of art that Landseer produced in the middle of the Victorian period, and in sculptural terms Sir Edwin Landseer did the lions in Trafalgar Square that face away from the column with Bailey’s form of Nelson triumphant and heroic at the top of the column, the whole thing originally conceived by the architect/sculptural designer William Railton.

Monument to Admiral Earl Howe, 1803

Yes, here we have a monumental piece in St. Paul’s Cathedral by the famous sculptor, John Flaxman, best remembered now in art history as a close friend to William Blake, who was then very obscure. It’s a heroic image of a British marshal and naval hero,[23] but again, you notice the overwhelming desire to classicize. Britannia is behind him with the trident. Various heroic maidens and sort of nymphs reach out to him in stone. It’s an absolutely enormous piece. Imperial lions exist to one side, looking slightly sleepy. This is the Earl Howe. You notice in its solidity and in its power and its monumentalism and its neo-classicism extreme imperial strength and total certainty. This is increasingly the sculpture of the nation-state that believes it’s born to dominate the planet.

Narcissus, 1838

Here we have a piece of high Classicism, or neo-Classicism. It’s in Flaxman’s spirit. It’s just on the cusp of the Victorian era in the 1830s. It’s Narcissus[24] as he stares down at a mirror or water, of course, in love with himself. A naked male. Highly Hellenistic and late Roman imperial. It’s part of what will become the quintessential sculpture of the Victorian period as chronicled by a historian called William Gaunt, in his two-volume history called Victorian Olympus.[25] This was very much the tendency that the middle to high Victorian period wanted to exemplify, particularly in what might be called establishment or top-down art. It was the belief that we are the inheritors of the Roman imperial tradition, that we were the new and the greatest empire since Rome, that we were increasingly coming during this period to dominate at best a quarter of the planet. This was the art reaching back 2,000, 2,500 years to the Classical dawn of our civilization.

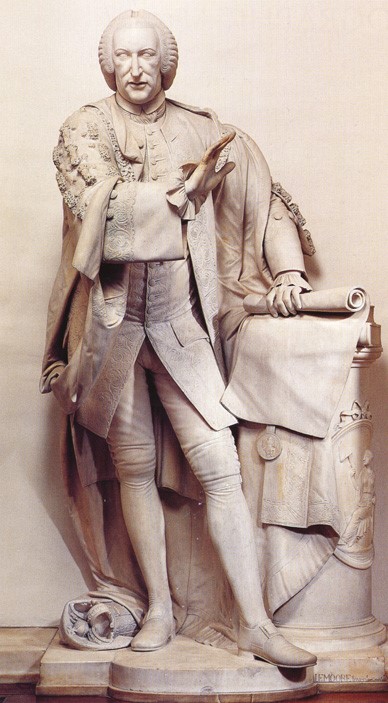

Lord Botetourt, 1775, photographed 1957

It’s also interesting to raise two cultural points here. The first is that this tradition sees Britain as the inheritor of the Classical world without any equivocation. The imperial or neo-imperial role of the United States in the twentieth century and official American art, particularly from the early part of the nineteenth century, is very much still in this vogue. The art of Washington, DC today is this type of art. It’s effortlessly imperial, not particularly Christian, and it’s essentially neo-Classical in an extreme manner. The other interesting thing to point out is that in the twentieth century, from a liberal perspective, this is the sort of art, certainly after the era of the Great War between 1914–1918, that will become associated with what will be regarded as totalitarian regimes of Left and Right.

Here is the extension of this type of Classicism to the New World, but it could be anywhere in England, Scotland, or Wales. This is from 1775. It’s a colonial piece[26] from the southern United States, from the state of Virginia. This would obviously be of the master and slave-owner of the period. It would be emblematic of the Southern ruling aristocracy that would only go down in the 1860s, that part of the century later in the Civil War. So, we’ve got a sculptor here called Richard Haywood and you can see the monumentalism of the piece. It’s at least life-size, as you can see from the people who are transfigured in the background of the photograph.[27] It’s raised — almost like a Donatello Renaissance sculpture from the middle of the second Christian millennium — on high. This was the Hellenistic pose of white rule in the 1700s on both sides of the Atlantic.

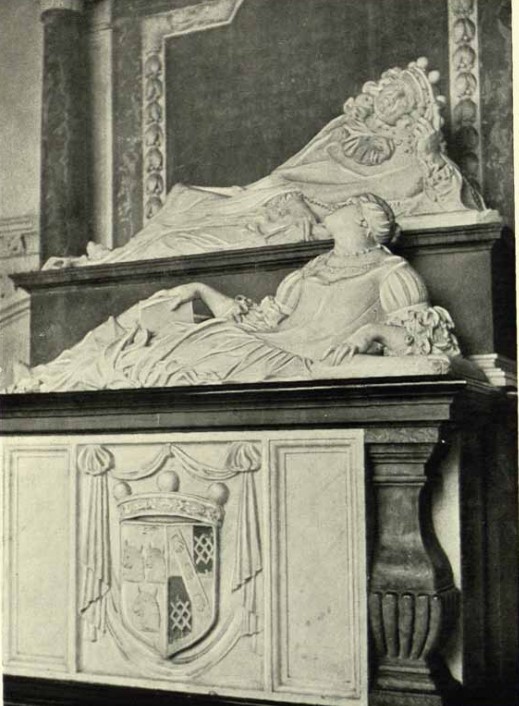

Sir Jacob Garrard & his son and grandson, 1727

Here we have a mausoleum. It’s from the Victorian period by Peter Hollins.[28] It’s of Mrs. Thompson, who’s probably an upper bourgeois as much as an aristocratic figure, maybe died slightly early in life and therefore the family paid for this enormous tomb in the local priory underneath some stained glass. The sculpture would be at least life-sized, and she’s depicted in a neo-Classical vogue lying on a bed which is actually her tomb where her corpse is. So, you see in this art the desire for resurrection of the body in accordance with high Anglican and post-Catholic sensibility. You also see the power of local powerful families. We’re seeing a situation where it’s not just the monarchy, it’s not just the aristocracy, it’s not just imperial rulers who think of themselves in this way, but it’s major provincial families within England in their own areas and localities, squires and so on, who want to see their corpses and their memories of themselves and their wives done up as if they were the consorts of Roman Emperors.

Alderman William Beckford, 1767

It’s again from the middle of the 1700s. It celebrates provincial strength and aristocratic license. It’s of Sir Jacob Gerard.[29] It’s from Norfolk, in the east of England. Here we’ve got a sculptor who gives a rather solid Classical and three-dimensional representation to a provincial aristocratic family. One is reclining and lying, presumably in death. Others adopt a Roman imperial pose around the near corpse. It’s again part of this transfiguring desire to see people in a Romanesque and imperial manner completely out of keeping with the society in which they’re living, but it’s this desire to see themselves as the repository of the Roman imperial and Hellenistic culture of well over 2,000 years before.

Here we have another life-sized piece,[30] Very much in a Classical vogue, but more after the realistic delineation of an eighteenth-century gentleman. This is actually of the Gothic writer William Beckford, who wrote Vathek, which is an extreme horror story in sort of high-art terms of its period. Quite militant, atheistic, sort of amoral, and he was a bit of a so-and-so. He’s captured here as he would have liked to have been seen by both himself and doubtless his favorable contemporaries. This is from Ironmongers’ Hall, and it’s by Moore. Again, the importance of these pieces is their monumentality. This is life-size in stone.

Monument to George N. Hardinge (1781–1808), 1808 [16]

Here we have another Classical piece[31] from St. Paul’s. Very sort of neo-Classical in feel. Idealized. A strong element of narratives creeping into sculpture at this time. This is from 1808, right at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It celebrates probably the death of a man in combat, maybe in the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary wars of the period. An angel has come down and weeps upon his tomb. A shroud has sort of been put on one side. The man, or the sort of transubstantiation of his corpse reanimated in accordance with the Christian doctrine of second birth, looks out into the distance. You see strongly elitist, hierarchical, and storytelling concerns three-dimensionally in stone in one of our major cathedrals.

Here we have another piece[32] which is almost a lying in state, really, but it’s of another aristocratic female lying side on, probably in a priory or vicarage in Kent. It’s again this desire to depict people in death in terms of Classical and Christian relief. There’s a certain heaviness to the piece. It’s very English, very stolid. There’s always been the view, particularly on the continent and by certain art critics, that English Classicism doesn’t work too well, because their comparison is always the Southern European tradition, when in actual fact it’s the same type of art, but it is a different version of it. It’s one in which some of the four-square and stolid values of English self-determination and three-dimensionality come through. From the very beginning of the sculpture that we’ve looked at in this short film, we can see certain abiding characteristics that pre-exist everything irrespective of style, time, and place.

Tomb of James Douglas (1662–1711), 1713 [18]

Here’s the Duke of Queensberry[33] from earlier in the period that we’re looking at in terms of this particular type of Classical sculpture. Sort of Restoration 1660 through to the middle and latter stages of the nineteenth century, when the style doesn’t change too much and is very much of a piece. This is by John van Nost. It’s in Scotland. It’s very ornate, and it’s quite Baroque in spirit. He lies in death upon a bed or a divan, sort of swooning and thinking great thoughts with several cherubs above him, and there’s a plaque that lists his honorific titles and so on. There’s a sort of Doric column next to him and an arch over. Don’t forget this is life-size, extremely heavy, and the point is to indicate breeding, monumentalism, importance, and a link to the ancient world.

Sir John Cutler (1607-1693) [19]

Here we have another classicizing piece, life-sized, from about 1685. So, quite a way back, but the style you’ll notice from the Restoration in 1663 through to possibly the Great Reform Act in 1867 is very much of a piece. You could almost argue that this particular relief could have been done — this particular relief done of somebody I think was called Sir John Cutler[34] — at any time during that period.

The Admiral Richard Tyrell Monument, 1770 [20]

The Bowler, 1825

This is a very large and ornate piece by Nicholas Read in Westminster Abbey, 1766,[35] again in a style we’ve become conversant with during this phase of the film and this historical period with which it deals. It’s a monument to Admiral Tyrrell.[36] Behind him in relief, you can see his ship. You can see battle scenes. You can see a sort of angel, or his guardian angel, or the spirit of victory, or his soul leaving his body in accordance with the doctrine of transubstantiation. You can see billowing sails overmastering the top of this angelic image and so on. It’s a very big relief with three-dimensional elements. Probably would have taken several years to actually carve and produce.

Here is a piece from the early part of the nineteenth century, 1825. The Bowler, from The Cricketer and The Bowler, from Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire by Henry Rossi. It’s a somewhat more populist work, this one, dealing with sport. The bowler, of course, is anonymous. It’s Classical in its deportment and delineation, but of course he’s clothed. And you see an encroachment of popular sensibility here, as well as a narrative element. It relates, of course, much more to the period in which it was produced than to notions about the ancient world. So, you’re beginning to see a sort of realism in certain elements even of Classical sculpture.

Tomb of Richard Ladbroke, 1730 [21]

Tomb of William and Elizabeth Crofts, 1677

Here we see another large mausoleum. It’s by Joseph Rose the Elder to commemorate an aristocratic[37] or very upper-class family. It’s in Reigate in Surrey. Dates from the early part of the eighteenth century. The figures are relatively small, or maybe the photograph is from a distance. They may be life-size, but an enormous, monumental edifice here. It’s virtually like a sort of rock wall in neo-Classical and heightened vogue dedicated to the power and magnificence of this provincial family, and it shows you the desire these people have to immortalize themselves as provincial imperial figures in their area to be watched by their own community, as they perceived it, forever and ever.

Here’s another of these increasingly Rococo pieces that we’ve been looking at.[38] A sort of heightened Baroque Classicism of an aristocratic couple gazing in an adoring way at each other, the female lying beneath the male. This is from Suffolk. The sculptor is Abraham Story. Again, we’re looking at the early part of this period, the Restoration through to the middle of the nineteenth century. This piece dates from 1678, and it shows, yet again, the ideals about themselves that the provincial English and British aristocracy had: a monumentalism, a heightened Baroque sensibility, a Classicism, and a desire to glorify in family, nationality, and self.

Field Marshal Earl Harcourt (1743–1830), 1832 [22]

Yes, here we have another rather Classical, not particularly Baroque, piece[39]. Quite heavy, solemn. A peer of the realm, a sort of imperial ermine. Again, this desire to present oneself as a Victorian gentleman, as a man of leisure, as a man of means, also as a leader, as a statesman, and something of a Roman Senator in modernity. Again, this sculpture will be full size and will be there doubtless on a tomb or mausoleum to be admired by kith and kin in Oxfordshire.

Sir Francis Page (1661–1741), 1730 [23]

Reverend Thomas Whitaker

Here we have another slightly ornate piece, again a tomb: two life-sized vehicles, aristocratic husband and wife. Bewigged, in his case. Staring into the distance. Quite opulent. There’s a slightly Baroque touch to it. There’s a column that looks vaguely Doric to one side of them, and an arch. Again, it’s designed in a provincial setting. This is doubtless in a probably quite small church in Oxfordshire.[40] It’s designed to indicate power, local resource, and that one is part of a higher civilization that’s solid, stolid, representational, and knows where it’s going and what it represents.

Right here we have another piece from Yorkshire,[41] Reverend Thomas Whitaker. Possibly a local, sort of near-the-edge Anglican to non-conformist firebrand or Evangelical preacher of the time. Stares out serenely, but with a slightly Puritanical face at his would-be congregationists. Again, you see even extended out to probably a member of the gentry who happens to be in the clergy the same classicizing and heroic tendencies. A virtual full-size replication of self, continuation of one’s bodily existence in stone after death, power, and permanence. A civilization that really was encyclopedic and thought that they could define everything, determine everything, knew what was what, and had the future in their hands.

Robert Southey Memorial, 1843 [24]

Here we have a slightly new type of sculpture,[42] not in its form or delineation. Still Classical, but you notice there’s a Romantic feel coming in. It’s quite naturalistic and realist, up to a point, given the classicizing tendency we’ve already mentioned. It’s also biographical. It’s actually of a person: Southey the poet.[43] It also relates to a new movement and a new sensibility in the arts, what will become the dominant tendency of the whole of the nineteenth century, and this is the Romantic movement. You notice he’s not wearing a wig. He stares directly at the sculptor’s eye, if you like. Although it’s in Westminster Abbey and it dates from the 1840s, Southey, a slightly forgotten early Romantic poet now who wrote a famous biography of the naval hero Nelson, looks out at you and is the dawn of a new sensibility: more representational, less idealized, and in their own minds, a return to natural forms.

Rear Admiral Charles Holmes (1711–1761), 1761 [25]

Here we have another heroic and classicizing piece[44] of a military figure, but he’s also partly dressed in the military uniform of a Roman commander from the ancient world, even though he’s got a cannon behind him and a coat of arms above. So, you’ve got this idea of modernity, cannon fire from the middle of the 1700s, and yet at the same time a Roman imperial statesman who in death looks out at the future and the past.

The Last Judgement & Memorial to John and Elizabeth Ivie [26]

Here’s an interesting relief,[45] even though the skulls are slightly three-dimensional, from Exeter in the West Country, St. Petrock’s Church, 1717, by a profound provincial sculptor called John Weston. It’s of Jonathan and Elizabeth Ivie, and you notice that the background relief which is above the figures and is sort of transfigured or transubstantiated souls, some of them bewinged like angels, very much relates to artistic works that could be done by Donatello or Bellini. With the skulls you have a Gothic touch, even though this is very much prior to the Romantic movement. You have in this art, deep down, a form of tomb art, really, an obsession with death and with decay, but also with finality. Don’t forget this was a world in which the next life was very close, was believed to be totally real, and the Christian way was to prepare for it. Therefore, the celebration of death in a manner which contemporary people would find very, very difficult to either stomach or understand was ever-present. To put your skulls on the side of a tomb to celebrate your life would have been regarded as normalcy for a high bourgeois family from the provinces like this at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Monument to James & Jane Dutton, 1791 [27]

This is a famous piece[46] dating from the middle of the eighteenth century by Richard Westmacott the Elder. It’s in Gloucestershire. The upper part of this powerful sculpture consists of a guardian angel seen in feminine form raising the top of a lid of a burial urn and sort of mausoleum. She looks down in a beneficent way upon the corpse who will now rise to ascension.

From the same image, we see the object upon which the female guardian, angel, or spirit looks from above to below. This is the skeleton of the departed, who is now released from the burial urn and is looking up as a sort of fleshless monster at the angel who is freeing him from death. He’s about to rise in accordance with the high Christian doctrine of the Second Coming and the resurrection of the body and the Second and Final Judgment when, according to this particular theology, all will be redeemed or cursed and thrown down into darkness and Hell, and those who will not will ascend into Heaven and will in certain circumstances achieve again their own corporeal nature. So, you’ll be reborn in life in death, even with flesh, but the bones survive and are being raised by this angel. There’s a strongly Gothic element to this piece, but again, you see the obsessionality with death and with the overcoming of death seen in terms of Classical sculpture.

William Shakespeare, 1740 [28]

Here with a high Classical image from the 1740s by Scheemakers.[47] It’s Shakespeare; you can see the beginning of the cult of the artistic personality in this work. You can see also the beginning of an almost cultic reverence for Shakespeare as a writer, which reaches a status of a secular god almost, in modernity, particular in anglophone culture. Occasionally regarded as rough and unhewn and Elizabethan and rather barbaric, Shakespeare comes in over stages and is gradually accepted despite certain Augustine and Victorian moral qualms with some of the plays or their style. Shakespeare is depicted as a heroic creator gazing upon the Muses, and this is the beginning of a Classical cultivation of artistic biography that will reach an apogee with endless versions of Beethoven’s face and upper body and torso and bust and so on in the nineteenth century atop almost every Victorian mantlepiece or piano. But this importance of the individual creative personality depicted physically becomes more and more apparent. Don’t forget we’re emerging from a period where priests, where warriors, where kings and queens were put into this form. Now the artist himself becomes the subject of his work.

The Death of Germanicus [29], 1774 [29]

Jeremy Bentham’s (1748-1832) “Auto-Icon,” 1832

Here we have another piece of a military character, drawn from Classical myth and history, the death of Germanicus by Thomas Banks from the 1770s. The naked corpse; warriors swoon around it, some of them peripheral figures, are almost in relief, their three-dimensionality is tapered and is moving back into the stonework — but the key central characters (two of which are youths or small children) are depicted almost three-dimensionally. The background characters, again, merge more into the stonework, so you’ve got this sort of relief tending to radical representationality. It is an attempt in high eighteenth-century formulation, to recap what they believed the sculpture of the ancient world to have been like and how it comes down to us both from Classical Greek sculptors like Praxiteles, but also from Hellenistic sculpture, dug up again, and made to bear witness in the imperial papacies of the higher Renaissance.

Here we have an extraordinary and interesting piece, which almost goes outside sculpture and then steps back into it again. This is of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, a key founder of modern liberalism as it’s come to be seen and practiced. He wears a sort of Quakerish hat, and this is his corpse. This is an example of corpse art, almost the first in the West. It’s called an auto-icon, and he believed that everyone should have themselves exhibited as a corpse, and as a sort of artwork/sculpture after death. This extant form is still around. You can still see it in the precincts of University College London and Senate House in Bloomsbury, if you notice his sort of decapitated head/facial mask, or one version of it, is between his feet. Increasingly, this sculpture is in very great disrepair. The head is believed to be full of maggoty blood and this sort of thing, because the non-cryogenic processes by which it was embalmed and created and frozen in time from the 1830s to today in the twenty-first century has gradually destroyed it. However, although this appears to many sensibilities to be ghoulish and freakish, this is part of a long Western tradition in its way. The death mask, the birth mask, the mask that’s taken from your face in adulthood — this was done for Keats, it was done for Beethoven, it was done for Cromwell, it was done for Napoleon, it was done for Wellington, it was done for all sorts of figures, and was regarded as quite normal.

Also, art and anatomy have always gone together, since the ancient world, and many artists see themselves [as] closer to surgeons in their coolness, coldness, and objectivity than they do to necessarily emotionally-based artists. It’s often a misconception of people who are never involved in the arts to think it’s all about emotion and not about reason. Bearing in mind that Western art is based upon the body, the cult of the body, and of the body’s decay in and towards death, is inevitably part of this. In anatomy, the tradition from Galen through Versalius and now through in the twentieth century to controversial practitioners of a sort of hybrid of the arts and the sciences such the German embalmer and contemporary anatomist Professor Gunther von Hagens are all part of this tradition that Bentham opened up with this piece.

What Bentham is really saying is: Here is my corpse, let my face and head be cut off and be used as something for people to look at, let my eyes be cut out and used as marbles by the children of tomorrow. It’s a totally materialistic attitude towards death that believes there is nothing after. One is reminded of Danton the French revolutionary who went on the scaffold, turned to the executioner, and said, “Show my head to the people. It’s worth looking at.”

Apsley Gate (Grand Entrance to Hyde Park), erected 1826-29 [30]

Here we have again a very Grecian model, it’s by Henning,[48] it’s from 1828, it’s of Hyde Park Corner. Of course, millions of tourists and native inhabitants will have passed this, sometimes without seeing it at all day-on-day in the center of London. It’s based upon the idea of the Parthenon and the Elgin marbles and what they meant when they were brought over from Greece, and it’s yet another part of the heroicizing tendencies of early nineteenth-century art — this idea that we were the new Greece and the new Rome combined, and that in a rather Christianized way we could nevertheless bring the solidity of the ancient world to the modern, particularly in relation to memorials that dealt with war and sacrifice.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892), 1857 [31]

Here we have a mid-nineteenth century bust and sculpture which depicts the artist as hero, for the very best artistic and yet heroic figure. It’s of the poet laureate Tennyson,[49] best known to middle-twentieth-century audiences by his poem to celebrate the defeat, as it were, of the charge of the Light Brigade. He’s depicted in a biographical, a representational, and a rather realist or naturalistic manner, and not bewigged, well out of the eighteenth century. A studied and sort of low-key heroic ombit to the piece, and yet it’s the artist as hero who gazes out with a solemn and mature gaze. It’s how they believed, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Classical world would have depicted by a significant writer like Dio Cassius or Pliney or Catullus.

Frieze of Parnassus, Albert Memorial (detail), completed 1872 [32]

Here in this sort of lineup, or column of figures[50] seen from the side, is a depiction in slight relief, but nonetheless three-dimensionally, of a catalog or chronology of British sculptors — famous ones, anyway. This is from the Albert memorial by Armstead and Philip, and many of the people that we’ve looked at in terms of their works earlier in this film are depicted here. Of course there’s a certain element of artistic imagination and license going on, because how would the sculptors entirely have known of the physiology of their forebears or predecessors, artistically speaking. But nonetheless we begin with Nicholas Stone, who we looked at several centuries before in this chronology. Bird is there; John Bushnel, whose eccentricities we mentioned at one moment is also depicted; along with Bernini and various people from the continent who infused the solidity of the English style with a certain Renaissance lightness of touch.

The Sluggard [33]by Frederic Lord Leighton, 1886 [33]

Now moving from the middle of the Victorian period toward its end, the Romantic movement has certainly infused sculpture. It took a long time. Painting would be far more likely to succumb to Romantic treatment, in terms of Constable’s[51] “we’re looking at nature,” Turner’s[52] in pre-Impressionism, or the sort of Salvatore Rosa view of nature seen in a gothic or troubled manner. Three-dimensionally it would be more difficult to bring in the Romantic idea — but here it is, in Lord Leighton’s[53] sculpture. Now, one thing that you notice is because the idealizing tendencies of Classicism are reduced, the sculpture is more naturalistic, and therefore the nude will obviously be depicted more sexually, or at least psycho-sexually. This caused, in the high Victorian period, of course quite a bit of consternation. But, if you like, the nude is becoming more real, and one has this paradox about Victorian culture that in its era, which is regarded by modernity as very repressive and judgmental, nevertheless its three-dimensional art is increasingly erotic in terms of the nature of the Classical tradition.

This tendency towards eros in stone can be seen even more in G. F. Watts’ Clytie,[54] which is a sort of naked back of a servant girl looking over her shoulder. You possibly realize that, given the natural art element of this sculpture, it couldn’t be done from the front, because otherwise it would be regarded as straightforwardly pornographic. So, we’re now seeing the naturalization of the Classical urge as, of course, photography begins, and photography will affect all of the arts to the degree that Romanticism begins to come to an end towards the end of the nineteenth century, and by the turn of the twentieth century is virtually over and is replaced in modernity by the sensibility which is now called modernism. But the engine for this change — amongst many, many other complicated factors — is photography. In painting, it forces people not to reveal the nature around them, but to go inside the mind in relation to fantasy and dream and so forth as firstly still and then moving photography, namely cinema, the art of the twentieth century, takes over the realist and representational role in visual art. Similarly, in sculpture a turning away from the body and in towards a non-organic art of individual sensibility that doesn’t relate to the society, but purely the psychology of the artist, begins the trajectory which is called modernism. What we now see is a splitting away of the Classical dispensation. And radical regimes, fascist and Communist, are the only currents in the twentieth century where the monumental and classicizing tendencies of the last couple of centuries within the West are to be found. Even that is complicated and possibly should be the subject matter for another film.

So, this finishes off our relatively quick resume of English and British sculpture stretching over several thousand years. We’ve decided to end our film at the beginning of the twentieth century, end of the nineteenth, and I’ve ended it here because the modernist sensibility then takes over. Personally, I believe you need another film about modernist sculpture, even modernist art — another two films, maybe — because this sensibility is a total change and a revolutionary transformation in everything. So, the Classical tendency; the Christian, humanist, and post-Christian tendency; the pre-Christian tendency — two, three, four thousand years of work really comes to an end at the end of the nineteenth century. The representation of the physical body perfect and imperfect then goes into film, into still photography, into moving photography, and then into mass cinema film as well as elitist forms of artistic photography. Obviously, if you stop many classical films and freeze the frame, you actually have both a representational painting, but also at times a certain three-dimensionality to the piece rather like Mantegna’s Renaissance paintings, which were a combination of sculpture and painting.

Now, if we look at the English and British tradition, you have examples like Behnes’ bust of Queen Victoria, idealized from before her reign really begins. You have William Anderson’s version of the Scottish laureate or moral laureate [Robert] Burns from 1854. You have, as we depicted earlier in the film, the version of Robert Southey which exists in Bristol Cathedral and was completed by Bailey in 1845. And we have two famous sculptures which I would like to finish on, both for aesthetic and political reasons.

These are the images of Sir Henry Havelock from 1861[55] and of General Sir Charles Napier in 1856.[56] These were by sculptors such as George Adams. Now, both of these forms are very interesting, because Ken Livingstone, the present Mayor of London, when he was elected wanted to tear them down, or at least remove them from Trafalgar Square, where they sit at the front of the square, often ignored in comparison to Nelson’s Column, designed by Railton, with Bailey’s sculpture at the top and Landseer’s lions equidistant from the pillar. Now, many people, hundreds of thousands of people, will pass these sculptures of Havelock and Napier at the front of the square going down into Northumberland Avenue, where the Ministry of Defence now is, and they will not know who these figures are. These figures are imperialists from the Indian raj in the nineteenth century. One of them is responsible for putting down the Indian Mutiny with quite considerable bloodshed, and it’s because Leftists like Mayor Livingstone know this that he wanted these figures removed. He couldn’t get them removed, because his importance and alleged civic esteem as Mayor doesn’t extend to the appurtenances of Trafalgar Square. He’s got no control over the statuary in the square. He can ban people feeding the pigeons in the square, but he can’t remove sculpture. So, what he did to get his own back was he had the empty plinths at the far corner of the square, which is adjacent to the National Gallery behind it and looks across to the Canadian Embassy on the other side — he used that for Turner Prize exhibit art, deliberately to get back at the authorities who denied the fact that he could get rid of Napier and Havelock from the front of the square.

Charles James Napier, 1856 [35]

So, in this talk about aesthetics and politics we come full circle, because the high Victorian, Classical impulse exists in the central square right at the heart of our post-imperial city, London, where we now have a sort of anti-British and unpatriotic Mayor who wants to repudiate the imperial past — the imperial past which has in fact partly led, among other factors, to London’s multiracial present status. Nevertheless, the thing he wants to remove from the square is the symbolism of the past, is the way in which it classed itself, is its classification of itself — i.e., its Classicism.

So, to end this film, I would ask people when passing across the precincts of Trafalgar Square to have a look at these rather strong, slightly dour, stolid pieces of English sculpture at the front of the square depicting Havelock and Napier as imperial warriors and heroes in a subdued Classical manner, the images and reliefs and bulk masses that Livingstone wished to remove to some obscure place in Sheffield or Bolton, where you would never see them again.

Notes

[1] Bowden is referring to the Torrs Pony-cap [36], found between 1820 and 1829 in the county of Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland. The original image Bowden presents is missing the horns found with it, but it is accepted that the pony-cap had the horns attached, and together they are known as the “Torrs Chamfrein.”

[2] Bowden is referring to the Gorgon centrepiece on the pediment of the temple of the Sulis Minerva [37], Bath, Somerset, England.

[3] Bowden is referring to the head of Antenociticus [38], pictured, found at the outpost at Benwell, at Hadrian’s wall in Northumberland in 1862. It can be found at the Great North Museum, Hancock, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

[4] Bowden is referring to the Ruthwell Cross [39], probably dating from the seventh century, in the village of Ruthwell, Scotland. The carvings depict various Biblical scenes.

[5] Bowden is referring to an eleventh-century carving at Romsey Abbey [40]. Despite being an “abbey,” Romsey abbey is a very large and ornate church dating back to 907 AD. This life-sized carving is on an outside wall and features the hand of God descending from the clouds above Christ.

[6] It is unclear who Bowden is referring to. He may mean Sir William Orpen, a First World War artist, in the sense of reinterpreting this style through painting.

[7] Bowden is referring to the Tomb effigy of Queen Eleanor of Castile (d. 1290), wife of Edward I, in Westminster Abbey [41], London, England, cast in gilt bronze by William Torell. Torrell is also known for his tomb effigy of Henry III.

[8] The bronze effigy of Richard II (King of England 1377-1399) on his tomb in Westminster Abbey. The effigy was made after his Queen’s death (Anne of Bohemia) in 1395 by Nicholas Broker and Godrey Prest.

[9] This polychrome alabaster panel is currently held by the British Museum, asset number 1101924001. It depicts Christ with a crown of thorns stepping on a Roman soldier (in thirteenth-century English armor) as he exits the tomb. Interestingly, the soldiers all sport identical drooping handlebar moustaches.

[10] Bowden characterizes him as “the Roman Emperor and once conqueror of Britain.” Caesar beat the Britonic army, but did not settle Britain or occupy it. The bust is part of a series of gilded and painted terracotta roundels at Hampton Court Palace [42], commissioned in the late 1510s. They were produced by Giovanni da Maiano, a contemporary of Michelangelo, out of local London clay.

[11] ‘Plate 182: King’s College Chapel, Screen, W. Face’, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge (London, 1959), p. 182. British History Online [43] [accessed 22 December 2022].

[12] The Wriothesley Monument in St. Peter’s Church, Titchfield. This is the tomb effigy of Henry Wriothesley, Second Earl of Southampton, with that of his mother Jane Cheney above. On the far side, unseen, is a third effigy of Thomas Wriothesley, his father, the First Earl of Southampton.

[13] Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, does indeed have his remains interred within this tomb, though there is no effigy of him. He appears as the kneeling figure on the right panel beneath his father.

[14] Bowden is referring to the sculpture “. . . on the west panel of the pedestal of the Great Fire of London Monument facing Fish Street Hill. It is a basso-relievo which represents the King affording protection to the desolate City and, freedom to its rebuilders and inhabitants.” The monument itself [44] is 202 feet tall (the tallest isolated stone column in the world) and can be ascended by an internal staircase to a public balcony, affording a view over London.

[15] They are now on permanent display at Bethlem Museum of the Mind, Bethlem Royal Hospital, Beckenham, Kent.

[16] “Queen Victoria, when Princess Victoria of Kent (1819-1901), 1829 [45].” Part of the Royal Collection Trust. Image from Sixty Years A Queen: The Story of Her Majesty’s Reign by Sir Herbert Maxwell, 1897.

[17] A life-sized marble statue in St Peter’s Church, Tawstock.

[18] Tomb of Sir John Thornycroft, carved by Andrew Carpenter (Andreas Carpentier) of London, in the south chapel at St. Mary’s Church, Bloxham, Oxfordshire.

[19] She is buried with her husband and child in a vault beneath the Stanhope Chantry at St. Botolph’s in Chevening, Kent, England. This pose specifically refers to her death during childbirth at age 22. The sculptor, Sir Francis Leggat Chantrey, lived 1781-1841.

[20] Bust of George III, 1773, Agostino Carlini RA (1718-1790)

[21] On view at Getty Center, Museum West Pavilion, Gallery W101.

[22] Sir Richard Worsley, Seventh Baronet [46]. This was commissioned during his time as a Member of Parliament for Newton on the Isle of Wight, something that probably at least partly inspired the aquatic-themed commission.

[23] Admiral Howe (1726-1799) [47].

[24] Narcissus, 1838, by John Gibson RA (1790 – 1866) [48]

[25] Victorian Olympus is actually the last in a three-volume trilogy covering Victorian art movements.

[26] Statue of Lord Botetourt [49] in front of the Sir Christopher Wren Building at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. The original (pictured) has since been moved and replaced with a bronze replica.

[27] Bowden is referring to a much lower quality photograph not used here.

[28] The recumbent effigy of Sophia Thompson (d. 1838) on her monument by Peter Hollins in the north transept of Great Malvern Priory Church [50]. She is depicted turning in joy at the moment of her death to see the risen Christ.

[29] Sir Jacob Garrard of Langford, Kent, First Baronet; his son Sir Thomas Garrard; and his grandson, Sir Nicholas Garrand. The monument is located on (British) Ministry of Defense property, in Langford Church, Norfolk, and is inaccessible to the public without special permission. All three figures wear Roman armor.

[30] Alderman William Beckford by John Francis Moore. The statue is of William Beckford, Senior (baptised 19 December 1709-died 1770), but Bowden mistakes him for his son, also named William Beckford, an art collector and novelist (1760-1844). The statue “shows a stately Beckford clutching Magna Carta in one hand and posed perhaps mid-debate [51].”

[31] Monument to George N. Hardinge [52] (1781–1808) by Charles Manning (c.1776–1812/1813) at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

[32] Elizabeth Culpeper (or Colepeper, Lady of Leeds Castle) at rest in Hollingbourne Church, by Edward Marshall [53] (1598–1675). Unusually for the type, her hands are not clasped in prayer, but with one resting by her side and the other resting on her chest in repose. The Cheney Family’s heraldic beast, a theow or thoye, is shown at her feet. It was a strange, toothy animal with cloven hoofs and a cow’s tail.

[33] Tomb of James Douglas [54], Second Duke of Queensberry (1662–1711), with his wife Mary, erected 1713. It is located in the Queensberry Aisle of the Durisdeer Parish Church [55], Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

[34] This is not the exact statue of Sir John Cutler [56] to which Bowden refers, but another life-sized sculpture of him made by the same artist, Arnold Quellin (1653-1686) (Artus Quellinus). Cutler appears in similar pose and garb. This one is in Guildhall, London; the one to which Bowden refers is in Grocer’s Hall.

[35] Bowden incorrect states Tyrrell’s date of death as the date of the statue. The statue was unveiled in 1770, after Tyrrell’s death in 1766.

[36] The Admiral Richard Tyrrell monument, Westminster Abbey, 1770.

[37] The Richard Ladbroke monument [21] in St. Mary’s Church, Reigate, Surrey. The sculpture commemorates him and his family and was made between his death in 1730 and 1793. The reclining Ladbroke is between allegorical figures for truth and justice.

[38] Monument to William, First Baron Crofts [57] (d. 1677) and his second wife, Elizabeth, Church of St. Nicholas, Little Saxham, Suffolk. [58]

[39] Field Marshal William Harcourt [59], Third Earl Harcourt, sculpted by Robert William Siever. Two were produced and stand in St. Michael’s Parish Church in Stanton Harcourt, and in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

[40] Memorial to Sir Francis Page [60] and his second wife by Henry Scheemakers in Steeple Aston church, Oxfordshire.

[41] Vicar Thomas Whitaker [61] by Charles R. Smith, 1822, at the Parish Church of Saint Mary and All Saints [62], Whalley, Yorkshire

[42] The Robert Southey Memorial in Westminster Abbey [24] by Henry Weekes, 1843, in “Poet’s Corner.”

[43] Robert Southey, 1774-1843, an English poet of the Romantic school. He is the originator of the story of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.”

[44] Charles Holmes by Joseph Wilton [25], 1761, Westminster Abbey.

[45] This funerary monument is at St. Petrock’s Church [26], Exeter, Devon. It was originally located at St. Kerrian’s.

[46] This funerary monument to James Lenox Dutton and his second wife Jane shows a risqué angel with a slipped breast rather carefully trampling death underfoot. The Dutton couple only appear in relief on the burial urn lid that the Guardian Angel is holding. The monument is in St. Mary Magdalene’s Church, Sherborne, Gloucestershire.

[47] Peter Scheemakers (1691-1781). This is in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey, alongside the bust of Robert Southey also pictured. A reproduction of the Shakespeare memorial with altered text is in Leicester Square.

[48] The frieze was undertaken by both John Henning the Elder (1771-1851) and John Henning the Younger (1801-1857). Although it is based upon the Elgin Marbles, it is not a direct replica. British art historian Dana Arnold comments that “the original intention was to create a scheme which was classical in essence, underlining the culture and sophistication of London and/or the monarch.” Rural Urbanism: London Landscapes in the Early Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). Original article at VictorianWeb [63].

[49] Bust of Lord Tennyson [31] by Thomas Woolner (1825-1892) placed in Poet’s corner, Westminster Abbey, in 1895.

[50] Specifically, the Frieze of Parnassus by Henry Hugh Armstead and John Birnie Philip, which chronicles historical and what were contemporary writers, poets, musicians, architects, and sculptors. The complete memorial is much vaster than the detail shown here.

[51] John Constable (1776-1837).

[52] William Turner (1775-1851).

[53] Frederic Lord Leighton (1830-1896).

[54] By George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), part of the Tate collection, ref. N01768.

[55] Major General Sir Henry Havelock by William Behnes [64], 1861, which was erected and remains in Trafalgar Square, London.

[56] General Sir Charles James Napier by George Gammon Adams [65], 1856, also resident in Trafalgar Square.