1,537 words

1,537 words

Editor’s Note:

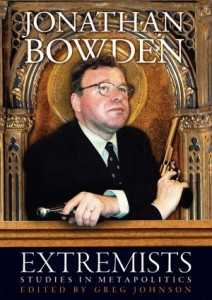

This is the transcription by V. S. of the Q&A session after Jonathan Bowden’s lecture on Martin Heidegger [1], which has been published in Extremists: Studies in Metapolitics [2]. The audio is below, and comes at the end of the recording of the lecture.

Q: I’ve noticed that Leftists systematically completely misunderstand what Heidegger meant by “nihilism.”

JB: Yes.

Q: In his conversations with Ernst Jünger, I think it was, he talks about how Jünger must inevitably pass through a period of nihilism. You know, it’s not that it’s good or bad. It’s just inevitable. You know, the question is whether or not he’ll come out the other side or not.

Now, I read that long, long ago before I ever tried to read Heidegger’s texts. Leftists, who have a prior investment in the idea that Nazism and Hitler in particular were nihilists in their point of view, they insist that Hitler had no principles, no values, and no ideals. He was simply a manipulator. Massive texts like Hermann Rauschning’s Conversations with Hitler were produced specifically to sell this idea that Hitler was a soulless manipulator. So, Leftists, having that background, when they read Heidegger’s remarks about the spirit of nihilism they think that it’s Hitler he’s referring to, but in fact it’s precisely the opposite.

Heidegger, I think, saw Nazism as a defense of Europe against nihilism. I mean, nihilism is related to Communism in the thought of that period. Communism is a reduction not just of ethics but of all philosophical categories to zero. So, the fight against nihilism, in his mind, would have been very similar to the fight against Communism, in Hitler’s mind, don’t you agree?

JB: Yes. And it also relates to ascetic ideas within religiosity. A soul, or an inner consciousness let’s say, a higher inner consciousness, fights against non-belief, against doubt, against unbelief, and so does a civilization. It wrestles with the prospect of meaning as absence, because if you can’t have that counter-proposition before you, like darkness and light or life and death, you can’t think without an oppositional polarity. Much of Western thinking proceeds oppositionally, proceeds by wrestling with that which needs to be overcome, because the idea of nihilism . . . Which in itself is also a very complicated idea, because is it possible for any period of time, for a group, or even for an individual to sustain what nihilism really means: the prospect of believing that everything is purposeless? Even the Sartrean idea that you step back from purposelessness and volitionalize it through commitment, again, is a denial of nihilism. He’s gone there and doesn’t want to stay.

Q: I think the relationship with Communism might lie in dualism. You probably might agree here, because you said something that suggested you’re a materialist yourself.

JB: Well, a Nietzschean.

Q: Well, the person who comes to mind is not really an ideal example, but Guénon, who argues in The Reign of Quantity and books like that that materialism is really a state in the process of reduction of the universe to absolute zero, to nil. I mean, it’s naturally the last stop before nothingness.

JB: Yes, Heidegger is within the discourse of Continental, advanced Western philosophizing a Perennialist and a Traditionalist, really, for whom the most agreeable semiotic of truth and purpose probably would be the Catholicism of his youth. But in actual fact, he doesn’t want to get belabored by that. He would much rather approach the entire question theoretically.

Yes, the interesting thing for most of our species though is that . . . Look at the Muslim world now. One truth, one purpose, death to those who are excluded from it, at least in accordance with certain definitions of it in a militant vanguard way. That is a type of militantly essentialist that the Western mind, in my view, can’t encompass. It’s not that it’s cretinous. It’s just that it’s not the way we perceive reality.

I knew certain Catholics who went and became Muslims after Vatican II. They left the Catholic Church because they wanted an absolute structure. They didn’t want any revisionism, if you like, within Christianity at all. They had to have total and utter certainty. And these were advanced people. These weren’t people lying in the sand being told what to think by a bloke who’s up there with a beard, you know. These are people who almost need that degree of certainty.

Most people are comfortable with no certainty at all. Liberals can live with unbelievable areas of uncertainty. Even the language they use. They’ll say, “Well, I do agree with you, but on the other hand there’s this proposition here but he’s got another view and, of course, that needs to be canvassed for reasons of inclusion.” And they’re hopping all over, because they can never draw it down.

Sometimes materiality is necessary, actually, to deal with elements of casuistry and relativism of the moment. Do you see what I mean? That it’s part of a concretization because liberalism itself has become so deconstructed even of itself, because I think contemporary post-modern liberal ideas are devouring themselves at a level of theory. They’re eating themselves up and, of course, there will come a moment when you do eat yourself completely and the only way to go forwards — the interesting notion of the avant garde in the last 200 years — the only way to go forwards will be to go back. Can’t go forwards any further. You’re never going to progress at all.

We believe in the idea that we should progress. In that sense, I’ve always resisted the notion that people well to the Right of that, which is regarded as centrist or even moderately Right-wing, are reactionaries. We want to progress in another area and go in another direction, and I personally think that these philosophical matters are of crucial importance, which is why at the material and political level, if you wanted to use this terminology, Heidegger made an extreme choice and, although an anti-existentialist theoretically, look at the choice he made, because that choice in ’33 wasn’t just to fit in cynically with the regime that had come in. It was a sort of total choice, a religious choice, really.

I suppose Evola’s partiality for the governments in both Germany and Italy, probably deep down more the one in Germany than in Italy really, was of a similar order. I think Evola said several things that in correlation to modernity there were several responses. One of which was to just join in, I suppose, one was to kill yourself and be done with it, one was to ground yourself in the essential purpose of prior traditions which were transcendental in character, and the other is Nietzscheanism, let’s put it that way. Sort of power morality and the prospect of self-transcendence outside systems in a world where all systems have collapsed or seem to have collapsed.

Q: I gather Italian Fascism is more based on Hegel via Giovanni Gentile.

JB: That’s right!

Q: So, that’s a big difference.

JB: Yes.

Q: You could say that as a kind of postscript about Hegel there.

JB: Criticizing him, yes.

Q: It is still possible to take Hegel seriously, in my view.

JB: Yes, the Italians did and . . .

Q: What’s the Hegel postscript?

JB: Let’s have a look.

Q: What? Hegel undermines what Heidegger was saying?

JB: No, that Hegel had interesting ideas about the conception of time and the ideas between time and spirit (Geist), but at the same time in some ways Heidegger is in a crude way playing whist, somebody who’s got a good hand that he produces an ace at the end and puts it down to say, “I’ve won this round.” So, there’s a little bit of that and that is in a sense Heidegger’s human element. The humanism of a non-humanist, if you like, the fact he could care what other intellectuals said about him and went to war ferociously against other detractors, of whom there were many.

Adorno was asked by a woman at a party once, she said, “Well, at least Heidegger, Professor Adorno, has placed man before death.” And he said, “Ludendorff did that.” Which is a good answer, you know, but so what? This is just salon talk, isn’t it really? In a way, Adorno is another rival absolute. Adorno sits there, you see those photos of him with one hand cupped in his face saying, “It’s all misery. The culture industry is everywhere. Everything is destroyed.” Interesting streak of conservatism in this high Marxist, if you like. Adorno is there, “Poetry after Auschwitz shouldn’t even be permitted,” which is one of his famous lines from Minima Moralia. “We should have no glory again because there’s been a few massacres.”

Well! Heidegger’s response would be, if he bothered to look at these things at all, that massacres are just a speeded-up process anyway, because life will end in the massacre of death, if you like. So, there’s a degree to which he would regard that as a moralistic and slightly bitter-minded remark outside the scope of true study, basically.

Anyone else got any questions, as the glasses are collected?

Q: Thank you very much, Jonathan!