Democracy: The God that Failed

From Richard Spencer’s Vanguard Podcast (audio, transcript)

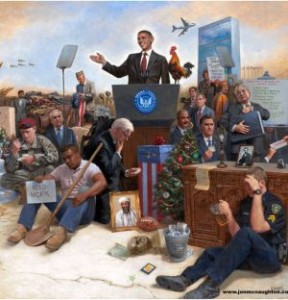

John McNaughton, Obamanation (detail)

8,195 words

Editor’s Note:

This is the transcript by V. S. of Richard Spencer’s Vanguard Podcast interview of Jonathan Bowden about democracy. You can listen to the podcast here.

Richard Spencer: Hello, everyone! Today it’s a great pleasure to welcome back Jonathan Bowden. So, Jonathan, how is everything over in England? I hope it’s not too dreary there in late January.

Jonathan Bowden: Not too bad, not too bad. It’s not particularly sunny. A little overcast, but pretty usual for this time of year.

RS: Very good. Today we’re going to talk about democracy. Democracy might be a kind of magic word in the English language and all languages in the Western world, if not the world altogether for that matter. It seems that everyone supports democracy. If you say something is democratic then it’s assumed that something is inherently good and so on and so forth.

And yet, at the same time, while democracy seems to be the most beloved form of government the world is almost universally unhappy with its leaders. If you look at the United States, Congress, which is the most democratic institution, at least as designed by the founders, they have approval rates in the teens or maybe as high as 20%. I’ve seen some single digits. They’re basically not popular at all. At least the last US president and Obama himself have become quite unpopular and if you look at the rest of the world it becomes even more interesting and perhaps the emotions are even more violent.

You can think in terms of the Arab Spring. Of course, in some cases those are reactions against leaders that were not elected, but even in Israel you had very strong public reactions against rightfully elected leaders. Things like the Occupy Wall Street movement and Tea Party certainly show that there is a powerful discontent in the air. It seems like all governments are unpopular.

So, we have an interesting world situation of democracy seems to be the reigning ideology and yet all of these regimes are suffering from a legitimacy crisis.

I’ve now set that up. Jonathan, let’s take a bite out of this topic by looking at something that I think all of our listeners can relate to and that is the election here in the United States. I have to say, it’s hard not to look at this spectacle which will cost billions of dollars and billions and billions more in opportunity costs. It’s hard not to look at these candidates and not come to the conclusion that they’re some of the most depressing, uninspiring, if not loathsome individuals that this country is able to produce. With, of course, the exception of Ron Paul who is a sort of avuncular figure who I respect, when I look at all the rest of the politicians I don’t have any desire to be governed by any of them.

So, what are your thoughts on this, Jonathan? We seem to be in a very strange state of affairs here at the beginning of the 21st century.

JB: Yes, I think democracy has not “had its day,” but it needs a bit of renewal from somewhere. The difficulty is to find out where it could come from. There are no marks at all for anyone who says they’re undemocratic or anti-democratic. I’ve always privately favored a sort of enlightened aristocracy, but that’s not coming back, enlightened or otherwise.

The difficulty is that if you excuse people from any say at all — and democracy is a very partial say, let’s face it — you’re left with a sort of emptiness at the core of citizenship, however defined.

One theory I’ve always had is that you would have graded voters whereby you would never take anyone’s vote away. They’ve got that now, and to take it from them in any sense would be widely seen as regressive. Yet, you might add votes to certain people. So, certain people that you favor. The philosophical gurus or people of alleged eminence might be given a million votes instead of one, and that might make things rather interesting in certain respects. But the old problem, of course, the old chestnut then comes up, “Who decides who would be given such a differential calculus in terms of what votes they could command?” So, you’re back to the old conundrum.

I think modern Western parties have become dreary and oppressing in that they tend to the center, which immediately puts a premium on philosophy of any sort. Anyone who is at all radical is weened out of the process and excluded pretty early on.

In the current Republican contest, only Ron Paul seems to have an agenda which could be said to be at all philosophical or ideological. Romney is an establishment and moderate-status Republican. Gingrich is difficult to determine from this distance. Sometimes he goes with the social conservatives and the Christians, sometimes he goes with the libertarians, sometimes he goes with the establishment of the party, and he seems to be a sort of megalomaniac politician from this distance on the other side of the Atlantic.

I remember all the fuss that was about him when he was a congressional leader a while back, but that’s fizzled out and tailed off. Again, viewed from a long way away and I’m not sure what his status is with the American population now and whether he has any sort of a democratic bounce in him or whether he’s just a stand-up politician because they want a contest and there has to be another candidate other than Romney for that to come about.

RS: I think the latter is the case. I certainly don’t understand it. And if you look at some basic polls, outside of the Republican electorate in South Carolina Gingrich is essentially hated. I also think he is a megalomaniac. I think all of these politicians are inherently narcissistic and kind of even sociopathic, but he seems to be a great megalomaniac without being interesting. He’s not exactly Captain Ahab or Macbeth or something like that. He’s a megalomaniac, but then when you learn more about him you wish you knew less.

JB: Why did he emerge as the Republican congressional leader so many years ago?

RS: I don’t know the full story. I think if you look at Newt’s life he’s always been kind of blustering and pompous and certainly has thought very highly of himself, and I think maybe you could just chalk it up to ambition alone. I think he was one of those types that always wanted to be in charge.

I know that one popular website in the United States they released a memo he wrote while he was an assistant professor, some very small professor, at a very small college in the South and he wrote a memo to the dean. I forgot the name of the college. It was like Backwoods College of Georgia or something. The memo was like, “Backwoods College of Georgia: The Next Hundred Years.”

He’s always been a very ambitious person, but again with other people of that sort they seem to have something interesting about them or you want to learn more about what drives them. But not so with Newt.

But what do you think this is about the kind of person that becomes a democratic candidate? I don’t think we should just look at the current ones we have now and say, “Oh, they’re a bunch of sociopaths and liars and used car salesmen” or something. I think it’s worth it to delve into that deeper.

I’ve always thought that democracy almost inherently favors this type of person who, on the one hand, is never going to offend anyone. So, he’ll never be radical. He’ll always try to please all. But also just the day to day of campaigning, the act of telling promises, telling everyone that you in a sense love them and they’re the greatest people on Earth and so on and so forth, the demands of that, the rigor of that, will lead to only sociopaths succeeding in a democratic system as we know it. What do you think about that, Jonathan?

JB: Yes, I think it obviously does favor a particular type of psychology. It does favor candidates of a certain type that will emerge over time. It does favor narcissistic and self-regarding individuals. It favors social psychopathic behavioral forms. It favors gratification exercises psychologically in terms of the candidate that rendered them closer to particular types of salesmen, auctioneers, actors and actresses, and all of these have been accentuated by 24-hour media and the need to appeal to such a media on a regular basis.

I also think there’s been a sort of downgrading of expectation. If you scroll back to the early 1960s and look at the Kennedy phenomenon when the Kennedys were considered to be, given the rapture that dictatorial figures are given within a plebiscitary democracy, there was this real culture of the Kennedys. There was a sort of quasi-erotic worship of the Kennedys as items, as movie stars, as moguls of politics.

Camelot was considered to be a sort of phenomenon in its own right. I think it’s the failure of Camelot and related projects — the scandal that brought down the Nixon dam, Watergate — the tarnishing of these quasi-authoritarian democratic figures. Kennedy very much on a level with Lloyd George in the British experience, who was only just about a democratic politician and who made an appeal to the mass electorate which was slightly undemocratic in certain respects. Churchill had an on-and-off reputation of a similar sort. It’s noticeable that would either of those figures and would Kennedy have survived in the present media bubble, given Kennedy’s extraordinary private sex life, had a scintilla of that been known about him in the 1960s that he was on these various drugs for ailments that he had that made him suffer from satyriasis, as it appeared. Just think what the 24-hour media and satellite news would make of that.

Clinton’s presidency was turned into a misery and an utter nightmare for infractions which were, on the Kennedys’ register, quite minor in the maelstrom of the early 1960s.

Similarly, Churchill’s private penchant for depression and extreme drunkenness and Lloyd George’s bigamy where he had two families going at the same time, one on the north of the Thames in London and one on the south of the Thames in London, when he was Prime Minister and when he was wartime Prime Minister at the height of the Great War, a war which Britain could very well have lost had it not been for his reorganization of the Ministry of Supply militarily.

So, I think a lot of democratic politicians are the product of the contemporary media circus. The fact that the flaws of would-be great men will always be exposed now but they won’t be exposed by biographers 40 years after their deaths, they’ll be exposed before they get into office and they’ll be exposed in the early stages of being elected by their parties. That’s before even the electorate gets to decide between them and other parties.

RS: That’s true. I don’t think a normal person would want to run for office. For instance, I’ve never been arrested or anything like that, but I’m sure, even when I look back over my relatively uneventful life, you could find something and inflate it to make me look like a maniac or some kind of reprobate. I think in some ways just a normal person who might have some healthy patriotic desires doesn’t want to put himself through that or his family through that.

Also, let me ask an even more jaundiced question. In some ways, do you think the people have gotten worse and more degraded? And what I mean by that is that if you look back at some 20th century democratic leaders . . . Churchill, to a degree, obviously had an aristocratic background, and he was clearly a great intellect. I think he was a great failure both as a military leader and a statesmen, but we can save that for another podcast. Charles de Gaulle and others like the Kennedy phenomenon and others like that, these were hardly perfect people, and I’m sure we have a wide variety of opinions on them, but they were in a sense better than the average man. The average man could look up at someone like de Gaulle and think that he’s a great man, that he’s someone worth admiring, he’s a military leader and so on and so forth.

I think now the people almost want a kind of person who is like them in a sense. I remember there’s this woman named Christine O’Donnell. I don’t know if news of her crossed the Atlantic. She seemed to be a well-intentioned woman and she was a little bit of a Puritan. Kind of a Christian Evangelical fanatic. I think she had a Catholic background, but she was an Evangelical Protestant. She was involved in some kind of rockin’ out to Jesus campaign and anti-masturbation campaign of all things, but I think what bothered me about her was she was clearly quite stupid. She probably had a room temperature IQ. She had nothing more to say than the nice girl at the coffee shop has to say to you. It just seems a little strange to elect the girl at the laundromat and make her a senator. I remember she had these ads where she would say, “I’m you.” That was the end of the ad. It seemed to be democracy in its essence.

But do you think, Jonathan, that we’ve seen a kind of transition from people wanting to look up to their leaders and now the public almost wants to elect themselves or something? They want someone who’s normal, who’s not going to offend them. I’ll just throw in here as well that Obama had a State of the Union address last night and I had better things to do than watch it, but I was just scanning some headlines today and one magazine put it through an analysis and it was actually at an 8th grade reading level, his State of the Union address. So, do you think things are becoming worse, that we’re entering a kind of idiocracy where essentially the masses will have boobs like themselves ruling the country?

JB: Yes, I think that’s what’s happened. I think anything great has about it the nimbus of the sinister and people have been taught not to want that anymore or are taught to be suspicious of it. In politicians of the past there was room for more character. There was room for more egoism that would show itself to the electorate.

With Churchill there would be moments of contempt, aristocratic contempt for the masses and with Lloyd George there would be moments of populist radicalism which were genuine rather than feigned, although he was a deeply manipulative politician in his way and a precursor to many things later in the century. He foreshadowed Roosevelt’s New Deal and all sorts of things. George was, in Britain, very much a prototype and a partial outsider as a politician as well. He’s an interesting example of someone who supported a pacifist course during a very popular war, the Boer War, at the turn of the 20th century when he was pro-Boer and anti-war and had to be guarded by the police because of threats to his life once at Birmingham town hall.

So, it was quite a radical figure to come in from that fringe to be the First World War leader and the great populist manipulator of the press and public opinion, but there’s no doubting whatsoever that these were gigantic figures in contemporary terms.

If you take politicians like Bill Clinton or John Major or Barack Obama or even Tony Blair, they’re cut from a much more minor cloth, and the public wants it that way otherwise there would be a yearning for greatness.

I saw over the weekend Ralph Fiennes’ modern-day version of Coriolanus, the Shakespearean play. Coriolanus is the type of leader who despises the masses and, despite being a military hero, is thrown out of Rome at the behest of the mob led by the tribunes because he won’t kowtow to the people, and he won’t give them even what passed in ancient Rome for what amounted to democratic sentiment. That’s one of Shakespeare’s less well-known plays from late in his career.

But that’s something which almost couldn’t happen now because there are no aristocratic strands in politics left. Politics is completely bourgeois and plugged into mass sentiment. Although some of the politicians, like David Cameron in Great Britain, come from an impeccably upper-class background, they’ve learned to play the game and the game is to be totally unideological, to be all things to all people, to give nothing away, to never say a remark that could be misunderstood, to never be sardonic or witty, because that’s dangerous. You exclude the majority from the debate, which is perceived as truculent and threatening. Never to be imprecisely precise, by which I mean somebody who gives loaded or slightly wolfish or dangerous answers to anything. You must never appear to be dangerous at all. Indeed, you have to campaign as an anti-politician essentially. Somebody who doesn’t really want political power and would never take a country to war, which is all very ironic because when these people get in, they hunger for political power as expressed and exercised and, in the case of the United States, are highly prone to take the country to war.

So, you almost run against what it is to be political, and in the United States you have a very radical formulation of this whereby all of these candidates declare themselves to be anti-Washington outsiders, which amongst many of them is totally absurd. Transparently so. They’ve been insiders from the very beginning. Possibly, from the perspective of Western Europe, a politician like Jimmy Carter, when he started out, may have been a genuine outsider and after the Republican White House mired in the Nixon scandals early in the ‘70s people wanted somebody who was an outsider. But nearly every major American politician, I would probably guess to include Ron Paul as well, is an insider. He may not be an insider’s insider, but the idea that George W. Bush could run against Washington is completely absurd. These are all pork barrel politicians up to their neck in favoritism and doing deals for people in their senatorial and congressional areas.

RS: Without question. Let’s put a little pressure on that. As you are saying, in terms of doing deals, we have a military-industrial complex that one can measure in the trillions. This is huge amounts of money. In many ways, we do have a ruling class and an aristocracy. However, it’s one that dare not speak its name, in a way. It’s one that justifies itself on not being an aristocracy or ruling class.

In terms of a lot of the financial elite, it’s literally invisible. I think that the average Joe on the street might see the politicians as the kind of rulers and he can strike out at one if he or she does some bad things, but obviously there’s a bigger and more invisible ruling class that has an immense amount of power. I’m, of course, referring to the financial industry, the investment banking industry, and things like that.

What would you say about this? We have a kind of strange ruling class today. It’s one that is aristocratic in the sense that you can actually define it by families and certain peoples and so on and so forth, but then it’s either invisible or it pretends it’s not what it is.

Now, you could expect that if you’re talking about, say, Wilhelm I or something he would wear martial uniforms, he’d have a certain flamboyance to his outward demeanor. He would say, “I am an aristocrat. I am a ruler. I am the state.” But now we have this ruling class that pretends it’s not a ruling class.

JB: Yes, it’s almost a Marxist idea, actually: the class that does not rule.

RS: Right.

JB: The ruling class that isn’t one. I think it all feeds into the idea that everything’s mixed together and in a strange, surreal way isn’t quite what it seems to be and that’s because everything has to be put through a prism of contesting itself before the people’s assent. I think you would find the ruling groups in Western Europe and North America will be much more naked and much more transparent if they didn’t have to consult the people every 4 or 5 years in what is a pretty minimal democracy, really. All you get is a couple of goes twice a decade, occasionally a little more, where you put a cross or a tick on a ballot in a plebiscitary way for parties that represent a range or spectrum of allowed and permitted opinion and for prominent personalities within those parties.

Usually, a lot of voting is negative where people are voting deliberately to keep somebody out rather than voting because they want a particular candidate. So, one wonders next time how many people will vote against Obama come what may whatever he said, how many people will vote along purely ethnic and racial lines in the United States where from a distance the Republicans seem to be essentially a White party with a few stringers and a few hangers-on from other groups. But essentially it’s the party White Americans feel comfortable in voting for and the Democrats have some working class White voters and union votes, but other than that are essentially a minority, ethnic mish-mash party with some feminist input as well.

You almost have a demographic deficit now whereby it’s going to be increasingly difficult for the Obama effect, in relation to the Democrats, to be resisted because I can see one of the two candidates in every presidential election, president and vice presidential candidate, being ethnic from now on into the future with the Democrats, because I don’t think they’re going to get elected otherwise. It struck me from a distance that Hillary Clinton ran a harsher campaign against Obama than the Republican official ticket did when it came to the presidential election. I may be wrong there because I’m viewing it from a great distance, but that’s what it appeared to me and I wonder whether she would have been the candidate of choice had it not been for certain ethnic changes in the demography of the Democratic Party which meant that in the end she couldn’t get the votes. She was carrying a lot of baggage from the first Clinton White House. That’s true. But maybe she couldn’t get elected because, basically, when you add up the Latino bloc and the Black bloc and the mixed bloc you’re not really going to necessarily elect that many White candidates again in terms of the Democratic Party.

RS: I think you’re right. What you’re referring to is also what I call the majority strategy. It’s something Sam Francis wrote about quite a bit in the ’90s and Steve Sailer has written about it more recently, as well as Peter Brimelow. It’s this basic idea that the GOP is relying on White Nationalism in a way. You know, I’m being a little bit cheeky in saying that, but people just get a sense that the GOP is not threatening to them, it represents their values, so to speak, you have White guys up there who aren’t really offensive, you kind of trust them more, and so the GOP gains power by White people rallying around it.

And yet overtly it is in many ways an anti-White party. I mean, I don’t think none of those people, even the Christian Right, or especially the Christian Right, would claim that this is an Anglo-Saxon country and that we have a long tradition with Europe or something like that. They’ll claim quite the opposite.

But then, on the other side, you have essentially, as opposed to the majority strategy, the minority strategy. But with the Democrats it’s totally overt. It’s, “We are the party of color, and we can obviously help our election prospects quite directly by allowing in more immigration and doing some amnesties here and there.”

Let me ask you, Jonathan, a little bit of a philosophical question. A lot of conservatives of the past — I’m thinking of people like Burke, but certainly many others and this would probably include, actually, most of the Founding Fathers of the United States — had a fear of democracy. They thought it could get out of control. They thought the people were too uncouth and too unsophisticated to make serious decisions. Essentially, there’s been a tradition of a conservative critique saying “we need wise rulers, might limit their power, but still we’ll have these people make sound decisions on the matter. We can’t allow populist sentiments and furious emotions to hold sway.”

So, in some ways, you can ask, “Is democracy the problem? Is it this mass frenzy that’s a real danger?” But you could turn that around and say that, “We have no democracy at all.” Every election that we have it’s claimed in the media and by all the politicians that, “This is the most important election of your life! You’ve got to go out and vote!” And yet nothing really changes. You might turn a knob here and tweak something there, but in terms of the general thrust of this country, at least, nothing changes. There’s more debt, more multiculturalism, more regulations of your life, more White guilt, whatever you want to say. It just keeps getting worse.

And I would say in the European context there are some things about it which are quite anti-democratic. Vlaams Belang was a legitimate party that achieved electoral victories quite rightly and yet it was kicked out of the government because it was claimed to be anti-democratic, which means they held views that the ruling order don’t like.

So, let me ask you, Jonathan. Do you think that in our age the danger is too much democracy or do you think that the danger is that there’s no democracy at all, that it’s all an illusion?

JB: Well, I think it’s true that we basically have democracy with a system attached to it and that system is liberalism. Perhaps the system could be called liberal democracy and you basically have to be a liberal to take part in the game. Partly a very real game, partly a charade that takes place in the democratic tent.

Liberals themselves understand that their system as it exists and can be described is a toss-up between pure liberalism theoretically and democracy. How much democracy you have can determine whether liberalism is endangered within the system itself. Liberals always worry about what will happen if people start voting for illiberal candidates in a liberal democracy. When do you choke that off? When do you say it’s illegitimate? When do you ban the parties of such people? Are you permitted to ban the parties of such people? Or do you just demonize them through the media and put maximum pressure on them in that way?

Also, there are religious and civic minorities, (32:27 ???) and so on, that perceive not to wish to part of a liberal democracy or if they do put up parties of a sectional and sectarian type are seen to be threatening in relation to liberal democracy. There numbers are not enough to achieve critical mass.

But liberals opine and wring their hands about these issues all the time. The limits to freedom within democracy and the degree to which they have to chop and change between liberalism and the democratic tenant. Some liberals will talk openly about dispensing with elements of democracy to preserve liberalism as a system. You don’t get that in the Anglo-Saxon world very much, but in continental Europe where things sometimes take a more theoretical cast of mind there are some people who will honestly talk in that way.

Others think that there can be no infraction upon democracy at all and you have radical libertarians, the Ron Paul type, who believe in the maximum participation and the maximum freedom of speech. Freedom of speech is highly curtailed in the Western democracies in order for multiculturalism to survive and for multiculturalism not to be threatened in any way. Indeed, there are probably more inhibitions in terms of mainstream freedom of speech and there are more things that can’t be discussed than ever before. All of it taking place within an atmosphere where everyone is told that there is maximal debate. Indeed, people have too much debate and there’s nothing that cannot be said and that censorship is the worst possible thing.

The grammar that liberalism polices democracy with is political correctness, which is a form of censorship. There’s no other way of looking at it if one is rational about it rather than emotive about it. You have a situation now where the slightest politically incorrect remark made by any candidate — Left, Right, or center, it doesn’t matter where they come from — the litmus test which is applied to them is, “Has their discourse been politically correct or not?”

Every time Ron Paul is mentioned on this side of the Atlantic some obscure journalism that was associated with him and that is regarded as “racist” is mentioned almost in the same breath and in the same paragraph. Now, I’m not close to the Paul candidacy from this distance, but I gather that it’s pretty small beer really.

RS: Yes.

JB: But it’s because they can link his name to something that’s incorrect, and if they could do the same with Gingrich, which they might be able to do given some of his remarks in South Carolina, which could be seen to be subliminally politically incorrect and group-oriented, then they will try to do so.

So, the debate is highly circumscribed and that’s because of the sort of society that you’re living in. All political correctness is, in a root way, is a way of giving inoffense to the overwhelming majority of people, because people don’t lose their group identities in a multiple group society. So, if people make the slightest comments that could be perceived as negative of any group numbering more than 10 people that will be used against them.

RS: Yes, I agree. Let’s move the conversation a little bit to the historical aspects of democracy. Just to set up this aspect of the discussion, there is an important distinction to be made between liberalism and democracy. If you define democracy as the will of the people and in some ways the will of the people could be to round up this minority group and ship them off or throw them off into the ocean or something. So, people would consider that shocking and completely illiberal and unacceptable, but that would be the will of the people if 51% of the vote decided it was so. So, there is a strong antagonism between democracy and liberalism.

Let’s think about this a little bit historically. I want to bring up the work of Hans-Hermann Hoppe, who’s an economist and political thinker. If you talk to your average Joe Bag-of-Donuts and you tell him about a king or an aristocratic ruler and you ask, “Do you think you are more free today?” I think the answer would most likely be, “Yes.” And probably an enthusiastic, “Yes!” But, as Hoppe points out, if you want to judge liberty by any real criterion then in the age of democracy liberty has declined precipitously.

If you look at rulers of the past: Genghis Khan — he conquered people with the sword — he would never conceive of taxing their income at the rates incomes are taxed in Europe and America. Louis XIV was not a totalitarian by any stretch of the imagination. If you look just objectively speaking, there was more liberty in his society than there is now in democracy.

And so I think why someone thinks they’re free now is they think that we are the government, so to speak.

What Hans-Hermann Hoppe points out is that earlier people would look at the state and essentially think that, “Oh, the state is doing that. The aristocrats are doing that. And that’s not me. They have their own interests, so I better keep them in check.” And I’m sure the state looked upon its subjects in the same light. There was maybe a good tension that was productive and kept liberty alive but then also allowed the aristocrats to perform their real function, which is the protection of the realm and the use of violence.

But we now have this illusion in the modern world that we are the government. So, in a sense, “We are going to go to war in Iraq. What tax rate should we have? What kind of immigration policy should we have?” This idea that we are the government.

So, this seems to be an historical consciousness of the highest order. It’s a big thing that people in the Western world, and really around the world, think. So, Jonathan, where do you think this is going, this “we are the government”? Where did it come from? Where is it going? And do you think there are any prospects that we might be able to move past this notion of representation or really identity between the people and the state?

JB: I think the only way you could get out of this conundrum is direct democracy, which Alain de Benoist on behalf of GRECE and the New Right has often advocated. This is closer to the type of democracy that exists in cantonal Switzerland, for instance.

Switzerland is quite an interesting example because Switzerland has avoided for most of the 20th century much of the things that have come in other democracies. They avoided participation in both great European wars, World War I and World War II, of course. The Swiss are highly privately armed and can put 2 million people in the battlefield with heavy military and armed training, and yet they haven’t fought a war and haven’t needed to for 500 years.

They’re also extraordinarily socially conservative. Women didn’t get the vote until very late in Switzerland. This is seen as regressive and unduly conservative by most champions of liberalism and democracy.

But there is something to be said for direct democracies. Certainly, the elitist liberalism that you have in the West now on all sorts of things, such as multiculturalism and who you go to war with and certain federal things such as the European Union in the Western European context, are decided for by tiny elites and the population is largely excluded and popular wishes in these matters are regarded as ignorant and ill-informed and are often against them are swept to one side.

Now, that doesn’t say too much for democracy, yet at the same time you have an ultra-democratic spirit that believes that everything needs to be put out to tender, put out to poll, and assessed by the popular will.

Direct democracy, where people decide on issues not on candidates and don’t vote for parties but vote for issues like, “Should we be inside or outside the European Union?” in the British context . . . Well, you’ll probably have a majority to leave the European Union totally contrary to the political instincts of the British ruling class, which contains a lot of skepticism about the union but always watches to remain within it.

One of the issues where liberalism and democracy are most fraught and at variance with one another is the issue of crime, particularly crime and punishment. This shows up a great difference between the United States and Western Europe. In Western Europe, liberal elites have contrived, basically by coming to dominate the thinking of these center-Right and center-Left parties in their respective parliaments, not to all mass instinct in relation to the issues of law and order to gain a hand. This is why punishments and so on for all sorts of infractions from the most serious to the least serious in Western Europe are considered by the populace to be absurdly soft and not stringent enough at all.

Whereas in America . . . Where I think . . . What is it? 37 states have the death penalty?

RS: Well, I’m sure it’s something like that. We have the largest prison population in the world.

JB: The death penalty in Western Europe is regarded as a sort of harbinger of political lunacy. Only those who are totally outside the system dare advocate the death penalty even though quite a few Tory MPs privately support it.

RS: Right.

JB: The last time there was a debate in the House of Commons on that was . . . A long time ago there was an attempt to frustrate the having of such debates, because it could canalize dangerous psychological energies on behalf of the masses. The masses support the death penalty 67% through 90% depending on the clientele of the poll and how you ask the question, but there is absolutely no question that the masses would be allowed to decide on issues like that where they would give regressive and reactionary answers according to the political establishment. Those views would be considered to be regressive and reactionary by conservative politicians in Western Europe never mind liberal or Leftist politicians.

So, there are enormous areas where the popular will is frustrated by the democratic mandate, and the only way that could be broken is if people decided on a six months basis on five key questions, which would be put out to referendum and put out to debate. The political class would say that this would end up in chaos because the masses don’t know what they want and could be easily swayed by demagogues and by media interests, which of course is a possibility, but we’d have a controlled management of mass instinct through liberal democracy and representative politics where often people get a version of what they don’t want and all they do is vote to prevent something worse.

RS: Yeah. Do you think also that the kind of world that de Benoist is imagining really requires a racially homogenous, and really culturally homogenous if not religiously homogenous, population? I agree that Switzerland is a civilized place. I’ve actually spent some time there a little while ago. I enjoyed it. They obviously have a stable and healthy culture.

At the same time, as an American, when I hear someone talking about direct democracy I can just imagine people voting on their television sets and voting the country free ice cream or voting that we should take away all the money of every person who earns more than a million dollars and give it to the people or something. You know, I just almost find myself siding with the bureaucrats on that issue. I think that a Swiss population could come up with some more sound decisions than America as it’s currently constitute could.

But maybe no population could. I’m not a fan of William F. Buckley, but he had a very nice line that is worth repeating and he said that he wanted America to be like Switzerland and he said that he was talking to a Swiss man and he asked him who the leader of his country was and the man said, “Oh yes, he’s a good man, but at the moment I can’t remember his name.” And Buckley, in one of his good moments, said, “That is a good political system where the population is depoliticized” in a sense. They’re not getting riled up by demagogues. They’re not watching Fox News every day. They’re living their lives, maybe having a family, maybe running a business or something. I don’t know. I think there’s something quite healthy sounding about an order like that.

Well, Jonathan, as we bring it to a close let me just ask you to look in a crystal ball for a little bit. What do you think is the future of democracy? I mentioned this when we first began this discussion that we had some time of stability, one could say, where the Cold War was ending, you had great big credit booms and economic booms in the Western world, we had notions of the end of history and so on and so forth, but we seem to be entering a new world now. I think things like the Arab Spring, maybe even Occupy Wall Street or the Occupy movement, are harbingers of this, that we seem to be entering a world where there’s going to be a lot more anger, there’s going to be a lot more people on the streets even in the wealthier countries. There’s just going to be a different kind of politics. We seem to be entering a new world.

So, maybe you could talk a little about what you see going forward and how democracy will fit in all this.

JB: I think it’s all determined by economic stability. The fact that Britain, for example, is a trillion pounds — a billion billion pounds — in debt this week, and although there are attempts, of course, to manufacture reduction in the budget deficit . . . If this ever triggered a major economic catastrophe such as has hit a small European nation like Greece, Iceland, or the Republic of Ireland . . . If a storm hit a major European country like Spain, Italy, France, or Britain — Germany would be much less likely on present scenarios — then I think all bets are off. I think you would see a fracturing in democracy. You would see a lot more generalized protests. You would see a lot more loutishness. You would see a lot more associated apathy. The two would go together. You would see a vanguardism by militant minorities, and you would see greater disengagement on behalf of larger and large republics.

I think that’s already accelerating. I think democracy will invert itself and become a purely minority game whereby in the future only important and triggered minorities actually vote. You may get a situation where 60% vote, but within that the election is decided by small, little groups that cross over party and other boundaries. So, the number of people who change their minds between elections and the number of voters who are targeted by one side or the other make the decisive switch.

I could well see a situation where democracy in the 21st and 22nd centuries approximates to democracy in the 19th century whereby you had a restricted franchise, and the majority didn’t vote because they weren’t able to. In Britain, all women couldn’t vote, and in 1867 key parts of the professional and upper middle class got the vote, but nobody else did apart for those above them in the hierarchy. So, a very small number of people decided the elections, but they were genuine elections.

I think what you’re going to have in the future is a very small number will decide them and yet everyone can still vote. It’s just the majority chooses not to.

RS: Out of apathy?

JB: Out of apathy, out of reverse anger, out of not understanding the difference between the candidates as the differences become more and more nuanced and less and less observable.

I do think the end of ideological politics in the West as it is perceived by many who belabor the fact that they can’t tell the difference between the parties anymore. The difference between the British parties is minimal. The difference between the Canadian parties is minimal. American politics I think, well, the mainstream candidates of a Romney sort . . . The difference between him and a centrist Democrat is, I would imagine, meaningless, really.

RS: Yeah.

JB: Only the injection of religion into politics, as it appears from a Western European distance, gives some sort of charge, partly to react against by some people, over the water in the United States.

But I personally predict that democracy and the liberal humanism that floats on it at the present time are going to be in trouble, but it’s going to be different types of trouble in different settings. In some places, it will be militant minorities going into the streets and courting trouble of all sorts. In other situations, it will be the apathy of the overwhelming majority.

There comes a point where in local elections and so on so many people subtract from the process, and you have 2/3rds not voting in elections in Western Europe, there comes a moment when those elections lose all validity. When the system itself becomes unable to operate . . .

This is true now at the level of the European Union. One of the reasons that the European Union can’t function isn’t because they can’t decide to go forward to a European state — a federal Europe, a USE. like the United States of America, the United States of Europe — or to backtrack to the nation-state . . . They are caught in the middle of those two polarities. That is true, but it’s because the European populations do not give the political class the endorsement required to make decisive decisions. That’s why the debt-based crises in individual nation-states can’t be ameliorated effectively. The popular will is important and mainstream politicians don’t have it and therefore can’t arrive at long-lasting solutions.

I think in the United States the inability that there seems to be to cut the deficit in any effective way and the logjam that appears from a distance to exist in congress now that you have a president of one party and assemblies of the other is all to do with the delegitimatization of both. I think Obama doesn’t have legitimacy, but apart from canalized anger in his midterm neither really do the Republicans who’ve come in to force him.

RS: Well, before we go, do you think that when this liberal age, or if this liberal age, really implodes on itself, if all those trillions in debt come home to roost that there could be maybe an opening for the kind of aristocratic politics that you and I would want to see? Maybe even one could gain power, certainly by force of arms, of course, but also one could gain power by charisma alone. When this whole order is delegitimized that people might begin to look towards someone who’s a kind of visionary.

JB: Yes, I think that could only occur if what exists now was totally discredited in the minds of the people who are alive now or in the future under such systems. I think that if such a discrediting did occur then all bets are off and although aristocracy in the sense of the ancient world or even 18th-century Europe prior to the bourgeois revolutions at the end of that century will never come back in the same form.

The notion of aristocratic rule could return maybe with a restricted franchise, maybe with an elect caste that’s seen to be the sort of philosopher-kings of a society, maybe with quasi-military figures who have to be civilian in order to rule but come from a military background, particularly if there’s a lot more social chaos around and that’s felt to be necessary.

But with 24-hour media, if the halters that liberalism provides that prevent charisma as an end in itself and prevents phenomena like a more aristocratic version of the Kennedys from emerging periodically and coming about, if those tendencies were annulled, arrested, or staid then you would see something else. I think that at the present time there are too many inhibitions that prevent the emergence of that type of politicking. People would always cluck as soon as it began to emerge that so-and-so is a dangerously authoritarian or sleek candidate, that so-and-so is a dangerously charismatic candidate and we know where that ends up, that so-and-so has undemocratic credentials or a whiff of elitism about them. Elitism, of course, being one of the most wounding politically incorrect charges. It’s not used very much because hardly any politician dares to make any elitist statements.

But as soon as the thing begins to tumble you will see elitist politics reemerge. It’s difficult at this stage of the game to see the forms that would take, but you’d know it as soon as you saw it. It’s only when the masses are prepared to embrace it again, because they would have to. We live in mass societies now. Even if the masses were prepared to have less of a say they would have to endorse that, paradoxically enough.

RS: Well, we can all hold out hope. Jonathan, thank you for being back on the program. This was a wonderful discussion and I look forward to talking with you again next week.

JB: Thanks very much! It’s been a pleasure to be here.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.