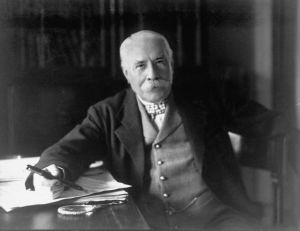

Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934), photographed in 1931.

3,636 words / 24:33

Editor’s Note:

This is the transcript by L. and D. H. of Jonathan Bowden’s talk on Edward Elgar, which was turned into a brief documentary with musical examples. To listen in a player, click here or below. To download the mp3, right-click here and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” Please post any corrections below as comments. If anyone has information on when this talk was given, and how it was turned into the present piece, please contact us here or post a comment.

We’re here today to talk about Edward Elgar, the great composer of the English renaissance in modern music — by which I mean twentieth-century music. There’s an enormous gap in our island’s musicology between Elizabeth’s time when some major, largely Roman Catholic, polyphonic composers like Byrd and Tallis and the first John Taverner and Davenport and others came to the fore, and Henry Purcell. Purcell lived in and around the time of the Great Fire of London from the restoration of the Stuart monarchy after the interregnum of Cromwell and the Civil War until the turn of the 1700s. He died, like Keats, of tuberculosis, so it is essentially believed.

Now, Purcell was a great genius of structure and order and composition and is described somewhat loosely as the English Mozart. Byrd and Tallis looked back through what for them was the modern idiom of polyphony to medieval plainsong and chant and high Christian Catholic music. We factor forward across two centuries basically, from 1700 to 1900, and there is not really an English composer of universal — never mind European — significance.

People come and go, and there are academic composers like Parry and so on towards the end of the 19th century, with whom Elgar was initially compared. But in actual fact, apart maybe from Sullivan’s Irish Symphony in 1864, there is not too much to speak of. What fills the musical landscape of our society during those 200 years is largely French and Italianate musical theater and opera, which, paradoxically, had begun back under the culture of the Puritans in the English Civil War where a lot of theater, including Shakespeare, was banned. But musical performances which were non-liturgical and non-religious were allowed. Therefore, women with large sort of busts and bodices and so on would perform secular pieces on stage, completely at variance with many Puritan ideas, but as long as it wasn’t religious it was okay. And that type of musical dramaturgy dominated our musical life for 200 years. And the view grew up on the continent that during the great era of largely Germanic symphonies, defined principally by Mozart and by Beethoven, we reached a position in England where there really was no music that was at all interesting or of universal import to the European civilization. Certainly, any music that could be talked about was parochial.

Elgar completely redefines the nature of English music, English classical music, and high art music of a British character. He’s also not a lone genius because, partly opened up by his example, there come several generations of composers who contain individuals like John Ireland was heavily influenced by him and Bax and Bliss, who wrote a lot of ballet scores, and eventually Britten and Tippett, despite his Left-wing views, and Birtwistle and Mathias, a Welsh composer of largely choral works, many of them put on by the BBC Third program as it was. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies at the present day, who looks to post-modernity, but also very early and even pre-Baroque musical styles to draw inspiration from, and then goes back up to the present day again to complete his cycle of eight symphonies and who lives up in the Orkney Islands is a continuation of a tradition that really began with Elgar.

Elgar moves English people in a way that no other composer — certainly none of those that I’ve just mentioned — really does. He speaks emotionally and from the heart and subjectively to the impressionism of the English. There is something slightly magical and indefinable about his musicology, whether people are listening to the sort of imperialist performances like “Land of Hope and Glory,” like “Rule Britannia” orchestrated by him, like Pomp and Circumstance, whether they’re listening to things to do with Victoria’s jubilee, or whether they go much deeper into works like the first two finished symphonies or the third symphony which would be finished from impressionistic notes long after his death by a contemporary, middling, and rather academic composer, or whether they’re listening to Cockaigne or whether they’re listening to The Kingdom or whether they’re listening to the mysticism related to his own personal Catholic faith of The Dream of Gerontius, his music draws English people in, in a way that really words cannot define.

There’s an interesting story that I’d like to share with you just for a moment that shows you the power of Elgar beyond all political and social affiliations as regards Englishness. Tony Banks is, in many ways, a very decadent and Left-wing politician who’s just left the House of Commons saying he despises most of his constituents who happen to live in a part of east London called Newham. Sixty percent of them are black, so I don’t know what that says about Banks’ particular take on all that. But he was a very Left-wing member of the GLC under Livingstone in the 1980s. When Thatcher shut that local authority down for internal political reasons within the British establishment — she didn’t like the way Livingstone was introducing taxes into London and so on, and was under business pressure to do so — the GLC on their final afternoon played Elgar throughout the three or four hours when the bailiffs were coming in to turf them out of what was then County Hall, which is now a private sector tower block.

And they played the Enigma Variations, and you had people like Banks who, in many ways, has been party to political and social programs and processes that have torn most of what this country once was down over the last 30, 40, 50 years — and he’s just one individual. But you have him in tears over the Enigma Variations, which represents the quintessence of Englishness. And you see the power even in the most unlikely places that this music has when it’s particularly manifest in relation to our nationality. There is something about the Worcestershire countryside; there is something about England, greenness and lushness and sweetness and harshness; there is something about the weather; there is something about the insularity both as a source of strength, of imaginativeness, of fairy tale lights, of romantic and imaginative introspection, but also sentimentality which is there in this man’s music and which, really, is in no-one else.

People like Purcell were great composers of the European type who happen to be English, but Elgar is a great English composer who is largely self-created because, unlike Vaughan Williams and unlike Bax who draw on a lot of Celtic folklore — but both of them went back to folk traditions that pre-exist higher or classical forms of white or Indo-European or Aryan music, Elgar created out of his own person; he created for himself in terms of his own deep emotional longing and desires. He also created in a very impressionistic way. After a day’s teaching, for example — because that’s what he did to survive for most of his adult life — he would play on the piano. He would play in an almost sort of stream of consciousness and free association way. He would note things down, how certain conjunctions of the diatonic register, certain forms of tonal composition, would work. He’d play them over to the wife again and note them all down. He’d go away and stick things to the backs of chairs in his study and so on and see that there would be an overlap between that piece over there and this bit over here, and, gradually, the texture of a larger work would be built up step-by-step organically, almost like pottering about your garden essentially in terms of his mental musicianship.

He was a very good violinist, a very good cello player when he was young. He didn’t really master any other instruments, but he became a major conductor of his own and other music, because British music was beginning to burgeon then, as I’ve already mentioned, towards the end of his life. He also hired many individual virtuosi and people who could actually play many of his pieces. It’s important to realize that there were several Elgars and that in many respects he was a very private man. His ultra-Tory politics and imperial manner and “blimpishness” together with figures like Conan Doyle, Kipling, and Rider Haggard and so on, many of whom in that Edwardian and Victorian era he was deeply, personally associated with and was friendly with, can give people the wrong impression about him.

There is a certain Leftist distaste for Elgar or for politics of imperialism with which he began Victoriana and with which he can be associated. But at the end of the day, he was a radical rather than a purely conservative, in the sense of restorationist, figure. He’s a man who wanted to bring forward a deep, romantic sensibility and articulate it through an individual vision of genius. Now “genius” is a concept itself which is unfashionable today, as is beauty, but Elgar believed in both. But true to a lot of English and British visual art, personhood and individual character — character above all — was supremely important. Elgar was, in many peoples’ minds, whether bohemian or otherwise, an eccentric. Amongst anglers, amongst people who like to row, amongst people who like to cycle in the countryside around where he lived, there’s a degree to which even amongst these rather more conventional and slightly staid, inartistic types he always stood out as a bit of an eccentric. Whereas amongst the artists he often brought to them the manner of the Victorian drawing-room and the Imperialist grand-uncle. So he existed as a “straight” amongst the bohemians and as an alternative person amongst people who were on a more conventional and bourgeois register.

Like all artists he existed between worlds, because the great point of an artistic sensibility is observation and analyzing life from without, because although his music is primarily about emotional sentiment, art is not a matter of sentiment. It’s not about emoting or sentimentality. Art is a hard, ultimately, rather than a soft discourse. Deep down it’s more objective than subjective. It’s the objectification which is what art is about, creating objects out of emotion. Science is about the objects of the natural world, of that which can be ratiocinated from the front of the brain, whereas all artistic matters are about emotion and lie deep in the recesses of the back brain in particular. But there’s a science of them, there’s a logic to them, there’s a knowledge of them and how the processes which connect with people’s emotions and are translated into form actually work. And music of all forms — which in some ways is why it’s always the most difficult to talk about in my view — is the form which is beyond all of the others because its language, its semiotic, is universal for all human beings within and beyond race. It’s almost the one art form that can impact on all minds and on all states of consciousness. Apart from the completely tone-deaf and deaf from birth there’s virtually nobody who can’t be moved by music. One pauses to think here that the greatest musician in the European classical tradition is Beethoven who was deaf for a significant proportion of his life and can hardly play properly towards the end, but the music was pure inside, and a lot of it was done by sight in terms of actual reading and close reading of the score. There are musicians to this day who actually relate more to the eye and the text, if you like — they’re textualists — rather than the ear, although for nearly everyone, of course, who works in the area it’s a combination of the two.

Now, Elgar epitomizes certain forms of Englishness which, for a long time, stood rejected at the heart of the continental culture. English music, even its revival, through Bax, through Bliss, through Vaughan Williams, through Ireland, through Tippett, through Britten, through Britten’s operas via Elgar, even looking back to people like Sullivan and Parry and so on, forward to modernists of a certain moment like Birtwistle and not Mathias but certainly Sir Maxwell Davies. Despite all of these and despite the recognition that continental musicology has given to them and large books by Germanic critics like Ernst Naumann have now been written about English music in the 20th century there is still this slight belittling of English musicology in continental sensibility, this sort of view that it’s all a bit Constance Lambert and a bit more, that it’s too saccharine, and it’s too sweet, that it lacks Germanic rigor and harshness, if you like, in these great architectural cathedrals of sound that someone like Bruckner creates, or pure concern with form or the expression of very lurid and over-the-top operatic emotion, that somehow there’s a certain quaintness to it, a certain shyness, a certain internal privacy, a certain softness and sweetness. This is, at times, a continental view of English music.

But this music that is Elgar’s — which is, racially speaking, a combination of Germanic and Celtic strands musically, within one particular personality — creates a feeling that English people respond to with deep sonorousness in joy and in sadness. And there is certainly joy and power and pageantry in Elgar’s music. But there’s also sadness as well. Because reading the life closely and with an eye upon the text you can really sense that there’s a bit of a sine curve in Elgar’s personality, and there are deep troughs as well as great ecstasies. There is the fact that after a major period of creation like the Second Symphony, he needed to rest up and couldn’t do very much creating for quite long time. After his wife died, I think in 1920 or thereabouts, there’s a great falling away. And apart from occasional pieces — an unfinished opera I think based on King Henry VIII — until his death, there wasn’t too much done. Elgar also realized that after the Great War there had been a high point of what critics would call jingoistic patriotism with which he had become partly associated, let’s be frank. And there was a great falling away of interest in his music during the 1920s. Although no-one, even his detractors, would actually say that he wasn’t very, very significant.

One piece that I would like to talk about in particular is The Dream of Gerontius, which is based upon a personal impression of Elgar’s religious ideas. His Roman Catholicism has never really been pushed that much although no-one’s particularly shied away from it in relation to his own specific biography. But it was there, and in an artistic way it was reasonably central to his life. His Catholicism had very little to do — if not nothing to do — with sectarianism. But what it was, was a personal religious tradition of transcendence, of the belief that you go beyond the body completely, which can lead in that theology to a disrespect for the body.

Jeff Rouse, The Dream of Gerontius

Now, The Dream of Gerontius is based upon a poem by Cardinal Newman. He was an important convert from the high Anglican Church to the Roman Catholic Church in England in the middle of the Victorian period, indeed the high Victorian period. He led a movement out of the clerisy of Oxford University at the time called first the Oxford Movement and then the Tractarians. To many people this is rather dry and archival and archaeological material, so to speak. But in the Victorian period for somebody important or for a group of people led by Newman to convert from the Anglican dispensation, which has now largely collapsed in our culture. Let’s face it, who listens to Rowan Williams now? For them to go over from that to Rome was an earthquake. It was a decisive change and it set people wondering what was happening to English Protestantism, so to say, in the 19th century.

The most mystical poem of a high Gerard Manley Hopkins type that Newman wrote was The Dream of Gerontius, upon which Elgar bases his particular work. There’s an interesting metaphoricization of this piece in the Elgar museum, which is a private sector museum based near Worcester. They’re very odd there, if you want to film about all this. You’ve got to pay quite a lot to go in there and so on and so forth. We went round the cottage where he was born which is turned into a museum. But an American contemporary sculptor, modern but traditional in casting, has done a metaphoric vision in stone but in three dimensions obviously of The Dream of Gerontius, and there’s a figure, which is the soul, leaving the corpse, leaving the body after death, and none of us knows what happens technically when a body dies but there’s a certain energy which is obviously in it goes. Because a cadaver is just an inanimate object whereas anything that has organic life in it is so qualitatively different to that which doesn’t, that something which was there is gone. The big question, of course, is where and what energy there was there has gone.

But in this particular relief the energy is going up out of the body and there are various sort of devilish, satanic creatures reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch and so on clawing around the bottom or the pedestal of the sculpture, trying to drag the spirit down into matter, into present day, into the somatic, into the bodily. And there are angels, or angelic figures of some description — because it’s not an explicitly Christian sculpture actually — moving the spirit upwards and outwards and towards the light. And Elgar is always concerned with, if you like, certainly in this piece, a certain lightness and a certain delicacy of touch; strength with delicacy; music in some ways relating to the spirit of dance although he never really explicitly wrote for the dance the way Bliss did with pieces like Checkmate later on, now which have been revived towards the end of the 20th century by sir Vernon Handley and his influence at Liverpool Philharmonic, for example.

Now, I see Elgar as essentially as a deeply individuated and traditional artist who is subjective, emotional, sweet-tempered, slightly melancholic, very, very English, and concerned primarily with transcendence. But there are also great moments of joy and that martial patriotism that the English have and which is a sort of pageantry. I’ve always been struck by elements of English nationalism within the British context and how they differentiate it from the more Celtic parts of the British peoples, such as the Irish, the Scottish, and the Welsh, against their own national feeling. There is in the English a slight softening or understatement of a more radical position and the need emotionally to express a radical feeling of patriotism and self-regard by using perhaps slightly softer tones and terms.

And this is why, in comparison to very militant expressions of national feeling, English people can stand to attention to things with sort of tears in their eyes and tears streaming down their faces and with extreme emotion and, sometimes, with very held-in violence as well that relates to these types of emotional forms that touch them very, very deeply and very much at the heart. It is that sort of belief that you can do an extraordinary thing and you don’t really necessarily want to be praised too much for it, at least in public afterwards. It’s that slight diffidence in the expression of that which otherwise would be radical which characterizes partly the depth of Elgar’s music, partly the fact that it’s a certain sense of English sensibility unmasked, and there are certain cultural criticisms of the English viewed outside in that see ourselves, see the English people, as in part wearing a mask. Elgar’s music is the emotional expressiveness of the English people unrepressed and without a mask, with deep sonority relating to private and yet personal experiences of a general, generic character. It is also expressive of the European civilization in high art music, but it is totally concentrated in the sensibility of these islands.

You can also hear a voice — a musical voice and a musical personality — coming out of this music from first to last. And when BBC Radio 3 in alliance with the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall produced the Third Symphony which is made up from scraps – absolute scraps and notes chucked about his study basically and pasted together by essentially an academic musicologist — immediately people realized it was him living again almost a century later, certainly 70 years later. And that voice, that sensibility, that sureness of note and pitch and tone came through yet again. And although maybe the Third Symphony, in inverted commas, has had much less impact than the first two, never mind the Enigma Variations, never mind The Dream of Gerontius, never mind the personal and impressionistic motifs based upon his friends like Jaeger and, later on, the composer Richter who took him up, notice again the Germanic influence that, although understanding the difference between the English and the Germanic, nevertheless cleaved to the English voice which was new and original and put the music of England and, later, Britain in its entirety back upon the map of European civilisation 200 years after the death of Henry Purcell.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.