H. P. Lovecraft

Aryan Mystic

19th New Right Meeting, London, February 7, 2009 (video, audio, transcript; reprinted in Pulp Fascism).

10,938 words / 1:08:41

10,938 words / 1:08:41

Editor’s Note:

This is a transcript by L. and D. H. of Jonathan Bowden’s lecture on H. P. Lovecraft, which was delivered at the 19th New Right meeting in London on February 7, 2009. Please post any corrections below as comments. The video is available below. To listen to only the audio recording in a player, click here or on the player below. To download the mp3, right-click here and choose “save link as” or “save target as.”

Now, this little talk is going to be on the horror and science fiction writer, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who has had many vicissitudes since his death, very early death, at 47 years of age in Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. Now, he was born in 1890 and during the course of the 20th century has become almost a cultic figure, alternately despised—Edmund Wilson wrote an essay in the 1950s totally dismissing fantasy literature of every sort—and yet now an enormous figure; he’s been raised to canonic status. There’s an official American Library of Congress-related set of editions in black, embossed hardback books of great American writers like Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, and so on, to Emily Dickinson, right through the 18th, 19th, 20th centuries gone. Lovecraft is now included.

* * *

Now, Lovecraft was an internet figure long before that was even invented, because he almost had his own media. At the beginning of the 20th century often people used to have amateur press journals of their own, which, if you like, are like a website or a blog now. And they would disseminate this material in certain cultural circles, particularly in the United States where there’s never been any statal or public provision for the arts until the Kennedy era, and where private patronage went essentially toward paying forms, where the idea of, in a Protestant and frontiers manner, producing culture for oneself or doing things and disseminating them in the way Ezra Pound did with his early volumes of poetry, was very much the vogue. And Lovecraft essentially published himself in small circles with others and then, through a publication called Weird Tales in the 1930s and ’40s, maybe late ’20s as well.

Now, one of the interesting things about Lovecraft is fantasy and non-realistic literature largely based on dreams and on phantasms and on nightmares, of course in his case, both real and metaphoric. Because that area was disprivileged, it was pushed down, down not just into popular culture or mass culture but even lower culture in a strange sort of way. I want to talk just for a moment on the culture of displacement. Many cultural phenomena can never be destroyed; they can just be displaced. If you look at the cult of the heroic and you look at certain classical and realist ideas, if you look at certain pagan ideas, if you look at certain ultra-masculine cultural conceptions, they’ve become so implausible and so disacknowledged within the post-War liberal dispensation that they’ve been pushed not to the margins of culture but down, down into areas that critics don’t even look at because they’re beneath that sort of trajectory; they’re beneath that searchlight, if you like, to use that term. They’re beneath that.

And if you look at a lot of comics or graphic novels and things that children and adolescents read—fantasy, adventure, escapist literature of all sorts—you certain primordial elements peeping out at you, often without any ideological or philosophical baggage at all because these are entertainment-based forms, let’s face it. And yet it’s quite clear that certain values are being disseminated by virtue of this type of phenomenon.

Lovecraft is famous today because he was once despised. He is famous today because he appeared in pulp magazines in the racks in drugstores and supermarkets next to the chewing-gum and that sort of thing. Because teenagers would save their small amounts of money to buy these magazines that were printed on paper that was so thin and so cheap that it was cheaper than newspaper print.

He’s famous now because he was in Weird Tales. Most of the stuff in Weird Tales of course hasn’t survived, although it’s interesting to notice that Robert E. Howard who created a whole cycle of heroic, masculine sort of figures, who engaged in sword and sorcery type dramaturgy on the page—Conan the Barbarian and that series of stories—is the most famous. But there were many before that. He’s widely known now and is a sort of cultural brand in his own right. Clark Ashton Smith is another one, and there are a few others—Donald Wandrei—a few others who have survived the demise of the magazine that gave birth to them.

It’s also true that modern capitalist or postmodern capitalist publishing likes a good seller and exists to make money, and, therefore, the science-fiction and fantasy areas—where H. G. Wells created with Jules Verne the form called scientific romanticism in the 19th century—now fill . . . If you go into Waterstones or Borders or any of these other bookshops—whole walls are full of this stuff because it is bought.

The interesting thing about Lovecraft is that it’s quite clear that most of his horror literature is based upon the dream. He kept a dream book by his bed and wrote down just the skeletons, these were the tropes—“hand in lake grabs child.” That’s all it would be. It’s a black fantasy if you like. And from that you embroider a short story of even a longish, multi-episode short story.

Horror and gothic fiction as the under-savage or blacker side of romanticism as a cultural dispensation, is very suited to the short story form. Because it’s intense, because it’s plot-driven, because it focuses around a dénouement that reveals the reality of the tale and what has really been going on and proses it, and, therefore, in an American sense, gives closure. And also because it’s concerned with externality, things that happen to people and things they fantasize about or configure before they occur. It’s not given over to very long novel length, discursive treatments of the inner mind, how people felt when these things were going on, and so on.

Strangely, in horror fiction at the contemporary moment, you get these great triple-decker novels that are this thick and are written by James Herbert and Stephen King and these sorts of people. I’ve only ever read one Stephen King book. That’s the one set in the hotel—The Shining—with the boy who has the second-sight. And the thing that struck me instantly, about 80 pages in, is I realized that the hotel is alive, that it contains the psychic memory of all the people who’ve died there, committed suicide there, done something destructive there, that the building is sort of seething with dark and negative energy, that it will take some of the characters over and destroy them, and that it will be the result, and probably it will blow up at the end. I suddenly realized “I’ve got to page 80,” because actually it’s 460 before you actually get to that moment. And it came to my mind that King is extending a short story out across 500 pages because his editor has told him “You’ve got to have a novel length, not a short story,” because the horror form, the gothic form, from Walpole, from novels like Vathek, from early 19th century literature, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when the Byron circle all sat round, and they all had to give a ghost story—remarkable set of stories came out of that particular evening. Polidori’s story came out of that, her story—although Shelley said he cleaned it up and improved it. I think she later wrote another novel called The Last Man. That was one that survived and Oxford Classics still do.

But why is it that particularly our people find the gothic form, find the dark romantic form deeply attractive as many of our people do, subconsciously, as I do? I think it’s because there’s a strength to the capacity to dream. It seems quite obvious to me that people like Poe and people like Lovecraft and other similar writers, particularly short story writers—Oliver Onions of the beginning of the 20th century—Elizabeth Bowen, the Irish ascendancy writer who wrote some very crippled, gnarled, ferocious short stories. Perhaps the greatest short story writer of this genre is M. R. James in the English tradition. He was a Master at Eton all of his adult life.

There seems to be, not just a desire to dream, but a desire to make the dream strong in the articulation of it. And strength in some ways means going artistically, if only for a moment, in a slightly sinister direction before you draw it back to have a resolution. It’s the shadow that the tree casts, gives you a three-dimensional insight into the reality of the wood. It’s almost as if it gives a visceral quality to that which could be softer and ethereal otherwise, and without that balance one can’t find a center.

Certainly Lovecraft never wrote any of the stories for monetary gain, although he did do the odd bit of ghost-writing, some of which is preserved. A book of the ghost-written material, the sort of touching up and receiving of the story and the recasting of the story in his own imagination, has been published just recently. Lovecraft is out of copyright, of course, now which is why there’s a great plethora of his material in the last year and a half.

His career began in isolation and seclusion. He was an only child. His father died in Butler Hospital in 1898 in Providence, Rhode Island. Don’t we hear in that name—Providence—the Protestant ancestry of New England? Salem, New Jerusalem, Providence—a people chosen by God, allegedly, leaving England to create a new world and a new dispensation. If you come from a town called Providence you sort of know that you’re part of the chosen and there in a differentiated way. He never lost that New England element.

Lovecraft always regarded himself as a Briton, even as an American. He didn’t like the American Republic—too modern, too new-fashioned, too new-fangled. Those people who didn’t really care for Washington’s revolution, some of them went to Canada; others called themselves loyalists or Tories, and they lived on in the United States and ultimately became a sort of gentlemanly cultural opposition to the nature of the American Republic, a looking back to the British past, a regarding that the United States was almost an extension of this country, that the theocrats who couldn’t basically create a Protestant dictatorship that lasted after the Civil War had before left to create a new one on the other side of the world.

Parenthetically, of course, although we’re talking about H. P. Lovecraft, I always use these talks to illustrate certain little things that are going on. We now we have the first decidedly non-European president of the United States of America. And it’s interesting to notice that apart from Patrick Buchanan there’s not one contemporary American politician who’s seen this event for what it is. And this event is a defeat, at least a defeat for one definition of America, for a definition of America that’s grounded in a post-European experience, for an America that is an expression of Nation Europa, for an America that is a nation demographically and, more importantly, culturally, for what David Duke calls European Americans. His victory is a symbol not only of what has occurred over the last 40 to 50 years, but also what the future holds. In most American cities, put rather bluntly, white Americans are in the minority now or, if they’re not, feel that they are. Therefore, his election on Latino, liberal white, black, and other votes is symptomatic of the way America has changed. Since the all-white immigration policy was done away with in the late 1960s, seventy million persons of color have entered the United States and changed it out of all recognition.

Now, Lovecraft’s America was white to a degree that many Americans now couldn’t even envisage, and yet he regarded it as appallingly decayed and decadent and utterly in racial chaos. And that was in sort of 1908, so what he would have made of 2008, 2009 is quite unbelievable. On his first trip to New York he said he was almost maddened by the seething whirlpool of the races and the destructive intensity of a world clashing upon the city. Because he was seeing it as someone who was very provincial—from Providence—transported to New York, the seething masses of New York, a sort of energy as they come in off the boat, and he sensed all that energy for both creation and destruction and, like all artists, would have been appalled and yet also excited—because energy always excites.

The interesting thing is his Wikipedia entry—don’t we all love Wikipedia, eh?—it testifies, “Lovecraft had certain views of a racial character,” and that is true. He was influenced not just by Spengler’s cosmology, of the undulation of cultures, of their design, of their relationships to theories of plants, theories of growth, theories of decay. If that has any truth to it, that book that came out called The Decline of the West at the end of the Great War, we are truly in an autumnal period. But as my edition of Chambers Biographical Dictionary tells me, Spengler’s views are only a theory. So there we are.

But Lovecraft was strongly influenced by him, strongly influenced by certain racialist writers like Wilton and so on, but also by the nature and temperament of his Protestant hierarchical and culturally elitist experience. As his major American/Asian explicator, S. T. Joshi, says, Lovecraft was typical of his era, and yet more typical than many, because it’s quite clear he had an ideological commitment to these ideas of decline and degeneration from which there could come new fulfilment and growth by virtue of reverse eugenisis or cosmological change or moral change or social transformation, whatever words or theories you wish to place upon it.

Always an eccentric, living at night like a sort of psychic vampire, writing gothic stories, living on a pittance, almost refusing to work because work was sort of slave morality, attitude of an old aristocratic past which his family had never really lived through. But, of course, the man is a writer of fantasy. His father died of nervous exhaustion, but he actually died of tertiary syphilis in 1898. His mother died in 1921, possibly of an infection of that sort. There does seem to be a little congenital disturbance in Lovecraft. However, the family had died around him and, as a child, they’d moved from quite august, large quarters to a very small cramped flat. This had a real impact upon the infant Lovecraft.

Lovecraft didn’t really go to school and educated himself, primarily in science. One of the interesting things about Lovecraft is it would be easy to look at him as an eccentric artist and a writer of Wildean, Swinburnian, Edgar Allen Poe-like short stories, a sort of New England gothic, as it could be described. But Lovecraft really was as much influenced by science as by the pedigree of artistic literature whether they related to the gothic area that he made his own or not.

One of the other interesting things about Lovecraft is he wrote an enormous number of letters. Rather like the compulsive e-mailer of today he would write 7, 10, 20 letters a day. His biographer in the 1970s—a science-fiction writer named L. Sprague de Camp (what a marvelous name, eh?)—was a sort of French American. He wrote over 100 books including some of the Conan cycle that he finished after Howard shot himself. Howard knew Lovecraft, of course. Howard was, again, an obsessive writer from Cross Plains in Texas. His mother died one day so he took a shotgun and blew the top of his head off the same day when he was 30. And yet he wrote before 30 years of age what many writers struggle to write in half a lifetime when all of this stuff was being published during the course of the 20th century.

But to return to Lovecraft, Lovecraft wrote over 100,000 letters according to de Camp. According to Joshi’s biography which appeared in the mid-’90s, he wrote about 85,000 letters. But in any respect he wrote an enormous amount, and many of these letters, because they’re often to quite famous writers and there are letters going back and forth, are being published over time. He also wrote five volumes of essays which have now been published and are now available via Amazon and so on.

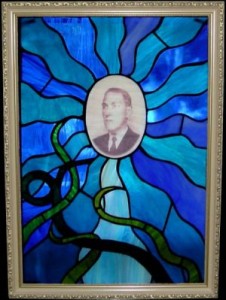

A cartoonist did an image of Lovecraft from earlier in his life dressed like Poe but further back, dressed like Poe as Dryden as Poe, with a wig, writing with a quill pen because pens were just too modern, you know, with bats and various things in the background, an image that appeals to his antiquarian bias, his 18th-century bias, his gothic bias, his image of himself and so on.

These essays are gathered together in five volumes as I say—one is on science, one is on art and literature, one is the amateur press journalism which is regarded as his contemporaneous material, one is on politics.

He began with a short journal of his own called The Conservative. Rest assured that was indeed a conservative journal in 1909–1910. In America, of course, the word “conservative” has totally different connotations as it does in the European continent. Because we’re so used to the center-right liberal party being called Conservative we actually have a slightly sort of Anglo-centric point of view of it. In France “conservative” largely means someone who philosophically rejects the tenets not only of the Enlightenment but of the politics of the French Revolution which is itself a radical or revolutionary position in relation to the last 200 years of French history. So the word “conservative” has quite a different connotation. In certain other cultures it can be considered to be, you know, the thing you call a party for people who’ve got a little bit of money.

Now, Lovecraft wrote about 30 stories including some juvenilia—three of them are long enough to be novels of a shortish compass. Many critics divide them into three—the period when he’s very much under the influence of Poe and Lord Dunsany and the Celtic, national Romantic traditions, slightly darker. It’s almost like the equivalent of somebody like Bates in prose. This is his early phase, more derivative in a way. The second phase is largely when the material becomes darker, stronger, less prolix, less baroque, more visceral and darker in tone. The third phase—the so-called cosmic phase—is when he introduces many of his scientific ideas into horror literature and when he develops a new vibration, a new discourse, a new way of methodologically capturing that era of fiction.

Traditionally it dealt with dreams; it dealt with interpretations of reality that come out of the Christian cultural legacy very explicitly; it dealt with diabolical possession or it dealt with demonic forces, or it dealt with ghosts, or it dealt with the concept of guilt, or it dealt with the ambience or sort of auric manifestations of place, of position, topography. It was very important in this type of genre of literature because you’re dealing less with fully wrought out Iris Murdoch presentations of personality, much more with mood, with atmosphere—mood within the individual and the environment that they shape and are shaped by. That’s why a lot of horror literature consists in a sense of building up an atmosphere of threat or plausibility or suspension of disbelief, particularly if it’s got any pretensions towards literature.

Now, Lovecraft at one level could be considered as religious in the sense that his work is so fantasy-laden and so imaginative, that it transports people into other realms. That’s why it’s remained so extraordinarily popular with adolescents. Adolescents often want primal answers, particularly about death, about human things, the morphic, and about decay, about radical things that people of slightly more mature years don’t wish to talk about quite so blatantly. They also love escape, and they also love adventure, and the idea of violence—action, if you like, appeals to them. I remember Evelyn Waugh once was asked “what was your favorite book when you were nine?” He said, “Captain Blood, because that’s what you want when you’re nine.” But not maybe when you’re 29.

Now, Lovecraft although he dealt in fantasy, was rhetorically and intellectually an atheist. He believed the imagination was our way to freedom by virtue of the fact that we were imprisoned within normative worlds of materialism, of mechanism, but also of chaos. Quite early on he imbibed an idea that the Modernist movement was to exemplify in many ways that has become rather a cliché now in that order is ordered and yet seething and pulsating as advanced physics allegedly tells us with the prospect of dissidence and decay. The point of the artist in this particular condition is to hold as much order as they can together amid the seething, indeterminate nature of the universe.

Now if we’re the prisoners of our genes, allegedly, if things are biological and morphic, if genetics (a term that wouldn’t have been used in Lovecraft’s intellectually formative era, of course, except by specialists) dominates everything, how can man be free in his own mind? How can he obscure the threatening nature of the universe? When Pascal looked out upon the universe at these great interstellar depths and chasms, he felt a strange emanation. He felt a cosmic coldness there and partly admitted, at least to himself as an internal reference point, that religiosity was not a way of dealing with that, as John Updike who died recently said, but certainly was a way through to dealing with that.

Few of us really can configure that if our universe is one speck of sand in the Sahara as certain cosmologists say, if that’s what this universe is, and there are universes upon universes upon universes allegedly clustered together in various ways, if the human mind on the edge of its consciousness can completely conceptualize this, even if most of these are theories that may be mathematically true, but we don’t know if they’re physically true or not—science in the future may determine that, may not—but Lovecraft’s way of dealing with this, a very modern way in actual fact, was to throw out the imagination, was to throw out the element of fantasy in the mind that which often in the child is permitted for the moment and yet is discouraged. The child wants to draw. The child wants to paint. “Don’t do that. Don’t do that” [slaps wrist]. You have to stop all that and get real and go into adult life and earn a living and that sort of thing at a certain time.

Lovecraft wanted to keep alive that facility of dreaming, to go onwards and to mature and deepen the nature of those dreams both positively and negatively. Indeed, in a way he’s only arguing for what many artists really do naturally anyway. Writing itself, in some ways, often people write about the nature of writing, particularly fictional writing, whatever area or genre they’re involved in, talk about the resistance to doing it before they start, then talk about slightly disengaging from the most conscious part of the mind. This isn’t stream of consciousness necessarily at all, because it’s deeply structured, deeply ordered in dealing with different types of memory and different types of the re-interpretation of things which you’ve experienced and made up even as you experience them. So quite complicated things are going on.

The nearest parallel that I can give to such processes is when you’re in an exam and you want a fact, if you screw your mind up and think, “I must have this fact, the name, date and so on,” you won’t remember it. But if you allow the mind to relax—which of course is difficult when people are under pressure—but if you allow that moment to occur, suddenly it comes back to you, just like that, just as if a prayer has been answered, because you didn’t force it, because you used a different part of your mind.

In many ways, I think this type of literature is in part about death. I think gothic literature is about death and about how you place yourself before it and how you deal with it imaginatively. Let’s face it, the one human experience which you can never write about afterwards is death. So, how do we pre-configure it in the mind in an advanced way? And this is actually extraordinarily human to actually configure this ultimate topic as a form of play, as a form of entertainment. People who like horror and genre and monster material and so on more than anybody else are adolescents, aren’t they? They’re young people. So right at the start you like the goriest type of material which you concede almost as a joke to yourself, partly possibly to hide the seriousness of some of the depths that it can bring up. So some very interesting things are going on here.

I’d also like to mention in relation to the culture of the far Right there’s a strong influence, strongly gothic in many ways, particularly in contemporary culture. In a post-Christian society which is morally dualist and where the values are in a very humanistic way of Christianity being secularized by liberals. As Iris Murdoch once said, we’ve kept the soft element of the Christian values and dumped the religion, and she’s saying the truth in relation to the mainstream culture that we’re in. Now, in relation to that liberal culture the radical Right, and certainly the forms of the Right that are to the Right of accepted Conservatism, have been demonized, haven been demonized in a way that you would almost demonize a rival religious tenet or opinion since the Second World War, and demonization works as a strategy. That’s why it’s adopted. It works in a way. But it also creates an enormous area of disfigurement, doesn’t it, and fantasy and illusion. Because people are attracted to the darker side even as they’re appalled by it. So as you demonize something you actually make it stronger at certain levels of psychological resistance.

It’s noticeable that in this society there are two tendencies of opinion that can’t be integrated. There was a Left-leaning form of Modernism called surrealism. We had a talk about Futurism earlier, which was of course Italian, and Vorticism which was British. Surrealism’s French and has no connection with the Right at all, because Breton aligned it with the French Communist Party of Maurice Thorez very early on. But surrealism broke apart as its leading gurus died after the war, such as Breton. Situationism, this minor shard, emerged, and this was the idea that all these tendencies were tied together, that everything’s the same, that everything can be made a joke of.

You go to the Eastern bloc and people are selling you stuff out of the back of vans and cars and thought this was petty capitalism, you know. There’s youth gangs around. Anthony Burgess went to Moscow and was appalled at the social disorder even under Brezhnev, and he based A Clockwork Orange and the gang culture that he saw, not on the ghettoes of Los Angeles, but on the ghettoes of Soviet cities where they developed this language of their own to exclude adults and exclude the police and this sort of thing. Burgess was a lecturer in linguistics and so was incredibly interested in this.

Now, Situationism has the idea that everything’s mixed together. There’s a bar that used to exist in Maidenhead called the Soviet Bar. This is after the Soviet Union has fallen. You can go into the Soviet Bar, and you can have a Dzerzhinsky. You can have a drink called a Dzerzhinsky. How many people in Berkshire know that he was the founder of the Cheka, one of the major mass-murdering organizations of the 20th century? But you can buy a drink named after him in Berkshire! That’s because nobody knows, and they’ve not got Google in front of them so they can’t Google it before they drink it to be offended. Do you know what I mean? But it’s the idea that something can be celebrated. The Red Bar—go in and have a Red! There’s a slogan above the bar that says “Drink as much as you want” and there’s a red flag next to it that says “Drink and be with the masses.” They’re making a joke of socialist realism, proletkult, because they’re spitting on it after it’s fallen. It’s been integrated.

But there’s two tendencies that can’t be integrated into Western life, that where Debord’s idea of the society of the spectacle falls down, and they’re the far Right and what’s called religious fundamentalism. They’re the two areas that can’t be drawn in. That’s why this audience will consist of far Rightists and some people who may or may not be considered by liberals to be metaphysical objectivists, which is the correct word for religious fundamentalists. That’s because these visions of reality can’t be integrated into the contemporary pea soup.

So the radical demonization of tendencies of opposition, with the British National Party at one end and Hizbut Tahrir at the other: liberals know that they can’t be integrated. They sort of break their teeth on those. They can’t be drawn in. Almost everything else—including the old far Left of the past—can.

This creates an odd energy. People are attracted towards that which is hated, particularly by power, but they’re also revolted as well. So there’s a division even in the nature of the attraction. People who’ve been involved in far Right groups for a very long time are aware of the psychology of certain of the haters, certain of the people who are most manifestly against, who are seething with anger whenever anything that could be attributed to the tendency that used to be called Fascism comes up. There’s an almost Pavlovian moment of hate, fear, and loathing that is often hiding and masking a quite subconscious feeling of attraction, which is not a foolish statement psychologically, otherwise that superficial reaction wouldn’t be as extreme. You don’t bring a rage against something about which you’re indifferent.

So demonization has all sorts of positively negative formulations. It’s also quite true that what’s called the Hollywood Nazi element has done no-one any favors at all, because you don’t have to be involved in the radical Right for too long to realize that there is a small number of people of psychopathic tendencies and all the rest of it who are attracted because it’s hated, because it’s regarded as evil.

I know when Winnie Mandela was demonized by the apartheid state she used to drive around Soweto in a limousine. The new black elite with their limos. And she had 666 painted on the bonnet because she exalted in being a demon, because she committed many murders of rivals in the ANC and so on. She had a crew of her own called the Mandela Football Team who used to do it for her, you know: “A necklace a day keeps Winnie at bay.” And how right they were! And she’s even been excluded by all the people who came in after her. But demonization doesn’t do people any favors at all. It’s certainly true that it terrifies many people in the middle, or of no views at all, which is the majority of people in a Western society.

I have gone slightly off the track in relation to Lovecraft. But the idea of that which is demonic, that which is “other,” that which is incredibly powerful, that can’t be mentioned, that can’t be named becomes a real force in Western society, and the literature of the Satanic, the pseudo-Satanic, outside of all religious constituted architecture becomes very, very powerful culturally and that’s what’s happened.

The far Right of course is one of the three views, if you like, about how the West should be organized—the radical Left-wing view, the centrist view tending to the Left which in a complicated way we all live under, and the tendency and opinion that was defeated in 1945, although it’s had other movements and so on subsequently.

So the demonic and the use of it in a dualist, very morally dualist culture, is very powerful. When Nietzsche wrote Thus Spake Zarathustra he brought back a Persian sage who institutionalized morally the idea that there was an absolute for evil and an absolute for good and they warred forever—the Manichean view, a heresy in Christian terms, the basis of Pauline Christian morality really. They needed a morality for this post-Jewish faith so they found one. When Nietzsche wrote that book he wanted this man from the mountains, if you like, to come back, this figure with the white beard and staff, and maybe a hat as well, you know—an iconic figure in all cultures.

He wanted him to come back and advocate non-dualism, the overcoming of the positive and the negative force and the institutionalization into one area and, in a way, gothic fiction you could argue is in some ways a recreational, entertainment-oriented version of that type of philosophizing. Because in many of Lovecraft’s stories, in many of Poe’s, in many of Hawthorne’s, it’s very difficult to see who’s the hero and who’s the villain. The villain is often circumstances of God, if you like, or it’s something from the outside or it’s something that’s very arcane. Even in relation to literature that’s very much more explicitly of the Christian period the idea that the destructive or the diabolical comes from outside is very powerful.

But, then again, if it’s to come from the outside and enter the inside of the human mind and purpose there’s got to be an entry point, hasn’t there? There’s got to be an asking of the force to come in. I remember at the beginning of Dracula by Bram Stoker, Jonathan Harker goes to the castle. Remember that magnificent scene in Transylvania. And he’s there, and the Count appears. The Count can’t ask him in. He’s got to ask for the door to open for all that to follow. He’s got to admit the force which, of course, is a religious idea. But in another way the force of destruction is willed. There’s a volitional element. It’s come inside.

I’m very struck whenever I think of the gothic tradition in our own culture by the great Scottish novel Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg, where at the end—and having built up the entire demonic character of this extreme Calvinist of this particular type in Scottish history—the Devil appears; the Devil makes a physical appearance, or sort of is construed in the narrative to have appeared, but if he’s there, he’s there, sort of steaming and so on. But you can read the entire novel that was brought back into modernity because it’s psychologically plausible to the modern mind and ear and eye and insight and so on, before you have this return to that which is otherworldly, that which is physically diabolical as the explanation for it all. For those who don’t know this novel it’s about an extremist form of Protestantism which is a sort of power moral novel, a sort of pre-Nietzschean morality.

Don’t forget, extremist Protestant ideas are very close to Jewish forms of theology, the belief that we are perfect, that we are the chosen. But if you say in a very ultra-Calvinist way, “I’m predestined. I’m chosen. I’m the elect,” can’t you step out of dualist Christian morality? “Morality’s for the others, for the sheep. I’m of the elect! I’m of the glorious!” This chap in the novel says, “My brother-in-law’s got a bit more money. I need to dispossess him of that money because I’m of the chosen. I’m of the Zion. We stride over the others.”

My mother was a Presbyterian. I once entered a Protestant chapel and they were all chanting, “We are Zion. We are Zion. We are Zion.” Now you know why Americans in the Deep South support the Israeli gunboats and planes as they bomb the Gaza Strip, because in their own minds they think of themselves as Zion. They think of themselves as elite. Because that wing of the Protestant religion believes those sorts of things.

Now, Lovecraft came out of that tradition and was formed by it even though he had a cynical an edge of the corner knowing, an artistic attitude towards it, because of course artists make play of, as well as celebrating, the traditions out of which they come. Conceptually now in the West, people who create say they believe in nothing. They’re just interested in everything but believe in nothing. This is the new line. This is the mantra. But of course without any beliefs there’s no creation because there’s nothing even to rebel against. There’s nothing there before there’s creation. So when people say they create out of Western culture but don’t really know what it is, it means they’re just stirring the top of a heap of dirt. Because they don’t know where they have come from. And the interesting things in the view of Obama’s election in the recent weeks is that people like Lovecraft are represented in America as a minority, even a minority/minority experience to the lives of most Americans.

But there is another America. America is not necessarily Pepsi-Cola signs everywhere and trash everywhere and so on. There is the tradition of Pound and of Eliot and of The American Language by Mencken and of the great literature that they could create as an extension of the European civilization and its mission. It’s not the America of MTV. But MTV’s controlled by a different ethnic group to these Americans, and what they did in relation to their past and any future they may have in that particular union. I personally—although it’s a long shot, a long punt, and we’re talking decades ahead—I don’t think white people have much of a future in the United States, particularly. They’ll be in a minority in the middle of this century. They’ll be armed to the teeth, everybody in their condominiums, they may able to move, and all the rest of it.

I was in Houston a couple of years ago. And you can fit England into Texas twelve times, and you can fit Britain eight times. And you get a publication, and it’ll talk about foreign news. The foreign news was what was happening in Oklahoma! Texas is so big that the rest of the world is nowhere. Henry Miller wrote an extraordinary book about the United States. It’s very odd to talk about Miller, a great sexologist, but he wrote this book called The Air-Conditioned Nightmare which is an extraordinary book of an old European sensibility about the United States. He said, “When you return from Paris to the United States, you know where you are because at the first gas station a Joe, a chap will tell you, “Isn’t it great to be back in the world, buddy?” Back in the world. Because America is so big that, to many people inside it, it is the world. The rest of the world is nowhere! America’s where it’s at, and you’d better believe it.

Although when you’re that big, when you’re putatively and actually that powerful, those are the sorts of beliefs that you will have. Any group would have if they’d amassed that degree of strength. The irony is that the intellectual brilliance of some Americans has been completely dis-privileged, and a mass low-level lumpen capitalist metaphysic has been translated as what America is all over the world.

The best thing that could ever happen to America in many ways is for all of their post-Imperial power to collapse and for them to go back to being the United States, to go back to being what they always wanted the country to be, which is a country of people who’d come from Europe to get away from all the fratricidal wars to build a new life. That’s why the most patriotic people in the United States advocate maximum isolation from the rest of the world.

That’s why when Gordon Brown gets on the box he says isolationism’s a great peril, a great danger. These protectionist people, these “British jobs for British workers” (his own slogan, of course!), these terrible people who want these sorts of things—American isolationists have always wanted it. The radical Right has always wanted it inside the United States, whatever its been called. Black America has always, until now, loathed the dispensation of the American state internally, has always wanted never to be involved in any foreign conflicts at all. America’s last war that they meaningfully fought would be the one over Cuba at the turn of the 20th century. After that, American isolationists would have kept out of any other war that didn’t relate to the Monroe doctrine and to what they were hemispherically.

Now, to return to Lovecraft! Lovecraft began as an Aryanist and as an American first, and up to a point. But he didn’t like Theodore Roosevelt because he wanted to go abroad. He wanted to manifest the American power externally. Because by the beginning of the 20th century America was getting very twitchy and would increasingly interfere not just in the Caribbean or Central and Latin America but all over the world. They tried one great attempt at the end of the First World War when Woodrow Wilson adopted a liberal mantra for American global hegemony and then there was a resigning from that, a retreat. Nothing is forever. America retreated from globalism once.

One of the most famous history books written in post Second World War America is Rise to Globalism by Stephen E. Ambrose. It’s totally mainstream. All of its views are utterly Harvard and CIA-appropriate and so on. It’s interesting because it’s such an insider’s view, and the idea that our Empire declines, of course. We once ruled quarter of the world in 1908. Look at us now. And our power was pretty straightforwardly taken from us by the United States, who’ve ruled in a neo-imperialist way since.

This is why American cultural figures—post-European figures in the United States—are so culturally important. Because whether they’re obscure or whether they’re mainstream, if they become mainstream, their culture’s ventilated all around the world. His books are in every bookshop in the world. He died when he was 47 almost certainly of semi-malnutrition because Lovecraft was so poor at the end he was living on baked beans, uncooked. If I was there I’d have said, “Look, Howard, you are starving to death, but couldn’t you think better than cold baked beans? Even a candle can heat it!” Put a tin there boy. Cheese and bits of old bread—that’s what he was living on.

So in a strange way it’s how the aristocratic sensibilities declined in the United States, because you can have an extraordinarily lopsided, gifted individual who can write great big thick books of no commercial value whatsoever, who’s not an academic, who can’t make money and whose family inheritance has gone in a world where, if you can’t make money, you’re nothing in the United States, where the only class they had of a higher sort was the slave-owning Southern aristocratic class that had gone down in the 1860s and had been completely destroyed in the war to end war in the States.

When I was in Texas you realize pretty quickly that people don’t, in the South, call the American Civil War “the Civil War.” You say the Civil War and they say, “What’s that?” You know, the Civil War. They say, “No—the war of aggression between the states; the war of northern aggression against us!” So it’s very important for tribalism that America’s not one country but many countries. Every tendency, every race, every culture, every religion is there now. So the America that Lovecraft addressed was largely a sort of organic culture—Indians and blacks excepted—in comparison to what it is now.

Now, Lovecraft’s later phase, which is called Cosmicism, is when he thinks of enemies of the human coming from the outside. This has led certain people to compare some of his work to some of Evola’s theories. It’s always said, and I remember well in a book a female academic in Northern England—a Jewish woman named Gill Seidel—wrote a book called Holocaust Denial. It’s published by a very obscure press about 15 years ago. And she said something very interesting in that book. She said, “All Right-wing discourse is an attempt to build hierarchy, and is an attempt to justify inequality, and is an attempt to exclude by virtue of its hierarchical ordination.” That is a totally truthful statement. It’s one of those moments when the outsider sees from the outside the truth of the discourse. Why do Right-wing sensibilities do that? It’s because they want to create order.

There are then debates about where the order comes from. And, of course, there’s two great views. One is the order is prior as metaphysically objective; in other words, outstanding truths, outside time, outside history, outside Man, outside his circumstances, where they are divine, where they don’t necessarily know everything that pertains to the truth of that, but they are prior to Man. That’s one of the views upon which we base the idea of a civilization. Not all of it’s made up. I hadn’t just thought of adding it today. That’s called heuristic thinking; you make it up as you go along.

The other great sort of polarity which is a more modern one, is people in a sense who can’t accept the religious verities of the past. Don’t forget, almost everyone in a Western society has grown up in a society where religion has crashed down around. It just doesn’t exist. I was born in 1962. The Christian religion, even if I had any partiality in that direction anyway, was dead. It had been really dying for at least a century in my mind, and the mind of many young people.

Now, in this situation, the one we’re in now, people of a rightist bias, if you like, in the last 200 years—someone like Charles Maurras, someone who actually founded Action Française thought, “I may not know what the absolute truth outside of this life that I experience is, but I can still support order and I can still support that which is given and I can still support prior structures that lead to hierarchical inequality. Why? Because they give meaning, because they lead to transcendence or the idea of transcendence which is the metaphoricisation of hierarchy as you go up.” Why do you want that? People say, “Why do you want all that?” You want it because it makes life deeper. It makes life more three-dimensional. It makes life more real. It makes the prospect of death more real. Why do you want that? You want that so you can be more alive. Then they stop saying, “Why do you want that?” because it becomes rather obvious. You say but that would lead, in some ways, to a tragic view of life or to a more profound view of life. And one of the modern conceits is to have things at such a low temperature, to have everything so boring, so nice, so compartmentalized . . . You feeling depressed? What a shock!

That’s what life’s about now in the West. The irony is many people from cultures from outside the West look on at us from the outside and think we’re all ninnies, and the truth of course is that the bulk of people here have accepted liberalism because their prior religion has collapsed, and they’re lazy, and they’re enmeshed in materialism, and they’re enmeshed in materialistic lives. You know, if their credit cards were taken off them they’d be crying. Our marines are crying when the revolutionary guards take their iPods away. I said if I was running this country the men who train those marines would be crying.

But there is a degree to which, if you like, a constructive non-religious-based view of Right-wing thought is also valid in this sense, because if a prior hegemonic religious viewpoint has collapsed many Left liberals would argue “just plump for what exists now.” Safe, utilitarian, global, market-based, we’re all the same, we all want the same things, allegedly. We all want to shop. We all have the same desires, an Asda in every street. You know, this sort of thing. But in actual fact we’re not all the same and we don’t want all the same things and we don’t have the same dreams or desires. And so Lovecraft’s literature is about some of those dreams and some of those desires.

In closing, particularly for people who’ve never read him before, I’d like to look at one story in particular called “The Dunwich Horror” which is very interesting. It’s about 60 pages long, and Lovecraft builds atmosphere amazingly with these long, archaic and baroque sentences that seem to go on for almost too long. The story is about an eccentric backwoodsman who’s a black magician and has a sort of circle or Sabbat up by these stones on the heath. Because he has such a Salvator Rosa imagination, Lovecraft could see a nice wood in sunlight, and what he sees is gothic gnarled trunks and the prospect of human sacrifice in the woods. That’s what he sees, when in actual fact it’s a nice sort of Woolworth’s postcard as De Sade, in his imagination, because he sees things in this dark sort of a way.

And the story involves always with Lovecraft, even at his fellow Americans, conceptual elitism. Because there’s this attraction to the barbaric, the instinctualism of the lower orders and also this moral revulsion as well. And also they’re the ones who will allow in the forces from without.

And there’s this decayed family—decayed genealogical line—called the Whateleys. It’s quite clear there’s a malformed woman in the family who allegedly has some sort of congress with a being of nethermost essence from without, and she has two children. The husband who’s left creates a dwelling inside the house where he drops all the windows and closes them down and he builds a wooden structure on top of the house—the idea of an extended padded cell, if you like.

This is very much a staple of gothic literature. It was always said of the old British aristocracy, the big family chain, you’d have one who was mad, one who was utterly insane. But you wouldn’t have him in the black wagon dragged off to the local asylum. You’d build a padded cell in your mansion for him. “Is that Jeremy screaming?” And he’d be there. “He wants feeding again,” and approached with a long pole in that sort of British way. In a way, this sort of literature is like the fulminations from that room, at a distance. And so he builds this structure onto the back of this barn.

There’s two brothers that come from this illicit congress with this thing from without. One can be seen, and he speaks this little hick dialect, this sort of New England hick, “I’m goin’ out in ma buggy,” sort of dialect, you know? And he’s always very tightly dressed, the idea being that there’s bits of him that could slip out that you wouldn’t want to see, bits that aren’t human, particularly from beneath the waist. The old idea of the hooves and what is above them, you know? And every time he wanders down into town to have a chat, to have a jaw at the local drugstore with a few of the characters who prop up these stores, he’s very careful about his diction, about his way of behaving, about holding his trousers up. As of course you would be if you were half demonic nether essence going down to the local store to attain provisions. Put yourself in the chap’s place! Then he gets in his buggy and drives back up to the family farm. All the time there’s incessant tapping and knocking from the creature inside the extended wooden balustrade that’s wanting to get out.

And, of course, there’s always a professor in Lovecraft’s stories of Miskatonic University or the University of Arkham or something like this, and he will say, “I’m very troubled by these stirrings among the peasantry out in New England, Arkham town. There are some very primitive unreformed types out there who engage in some very strange rituals after dark either involving some strange mongrelization involvings things from without, things that can’t even be discussed, strange tappings at night, wooden promontories on the extensions of these clapperboard dwellings. I told these to my colleagues but they think I’m maaaaad. They think I’m totally insaaaane! I mean to quest out these provincial outposts and rec ’em in.” It’s always Lovecraft’s personality as the academic bachelor of means who wants to go out and see what the dark side of New England peasantry’s up to.

So, of course, things take a pretty turn when one of the brothers who’s a sort of half morphic and shape-shifter and semi-diabolical bit of a goat (completing the picture) dressed up like the Black and White Minstrels, breaks into the Miskatonic University to look at the forbidden volume. Lovecraft, like all bibliophiles, loved what post-structural critics call inter-textuality—the fact that one book leads to another book leads to another book that leads to a reference in a footnote that leads you back to another book so you become completely sort of imprisoned—a glorious imprisonment—in the world of books.

There’s, in some ways, a sort of anti-Fascistic novel called Auto-da-Fé written by Elias Canetti about a crazed bibliophile who lives increasingly surrounded by books and the books get closer and closer, you know, so they’re almost toppling over him. They’re almost sort of animate things about to destroy him, and he needs his crude housekeeper to keep the knowledge at bay. It’s a satire on the mind/body split in Western civilization where intellectuals become so lop-sided they almost topple over because the physical bit gets this small, compared to the brain, metaphorically.

But with the Whateleys—this demonic family—he breaks into the University to consult the Necronomicon, this book that Lovecraft made up of forbidden lore written by a mad Arab, and the ink is the sort of inner blood of a tarantula and so on. And the mad Arab is writing these sayings that the nether-gods are telling him in a spidery hand. It’s marvelous stuff, you know. And Whateley breaks into the library, “I’ve just gotta git what that crazy ol’ Arab was into, ‘cos I feel somethin’s a-comin’. Somethin’s a coming, and I gotta see this book.” And he’s caught in the University library trying to get this volume, translated in Lovecraft’s spiel by John Dee who was a famous magician and famous writer in that era of pre-science where magic and classical lore and extreme learning and arcana and madness all sort of gel around in one sort of area. How a backwoods peasant who’s got goat’s hooves could read Latin written by a mad Arab is not dwelt upon because of course in this literature you don’t need details! That’s for the critics. That’s for the Edmund Wilsons of this world, not the adolescents reading this sort of stuff.

And he has all these sorts of sigils and strange terms that when he speaks to his father about the Old Ones—the ones out there—at the Sabbat, he’s going to “Bring down! Oh the glee!”

By the end it’s the simple ones left at the turning by the cart who see him as the sort of half-brother morphic form, the other thing that was mated at the Sabbat hidden in the farmhouse by the wooden extension that then burst out. They’re the ones who see it, not the intellectuals. And they come back. And the New England rural citizens are on the ground rolling around saying, “Oh my God, I saw it! I can no longer see.” It’s like the blinding in King Lear in reverse.

And the professors ask them to recount in their own words—which gives Lovecraft the chance to do the sort of hick dialogue that he loves—about what they’ve seen. And one of them, a couple of whiskeys down the throat and the tie released, says, “I saw it, man, I saw it! It came out of the farmhouse, big like a cloud, but brown, and it wasn’t human, you understand? It wasn’t human at all! It was writhing snakes, snakes afresh, and they were gray going on pink. And each hosepipe, each thing had a sucker, had a sucker like a mouth at the end of it. Some of it was green, and some of it was violet, and some of it was brown, and some of it was some sort of color you don’t even want to think of, and on top of it was this great sort of a disc.”

“A disc? A metal disc?” You know, the sort of obtuseness of the academic mind that when they’re being told about an enormous monster coming out of a farmhouse they want to sort of get it down what sort of disc it was on top. Yes, of course. “I don’t know, professor, some sort of a disc, and it was coming out of the farmhouse like this! But that wasn’t the worst.” And the academics are going “Not the worst, boy, not the worst?” “No, on top of this disc-like mongrel entity of flesh and suckers there was a face! It was worse than a face!” “God damn, what’s worse than a face?” “On top of a critter like that, boy, what’s worse than a face is half a face.” Because it’s got half the face of its brother on top of this great seething mass as it goes up.

And then the professor ends his tale by saying, “I know my fellow academics will not believe this occurred. It’s the testimony of simple backwoodsmen. I know that for many you sitting in your hearths and booths stories of farmhouses exploding unleashing demonic things with faces on top of hosepipes blancmange are not your cup of tea. But I am saying, as Jesus is my witness, that I saw it. But actually I didn’t see it, actually. But it was recounted to me by a man who knew and he saw because there are evil people out there like the Whateleys, and they want to bring in these things from the outside, and it ain’t permitted, you understand, to bring them in without a by your leave. We came here to New England to build a new world. And these low-grade peasant types with their primitive folk religions are bringing in these creatures from the outside. But I tell you, the professors of Miskatonic will stand against it!” Well, that’s alright then, isn’t it? The idea that they will stand against the nether forces of the dark that are always brought in by those who are more primal, and then the story ends.

“The Dunwich Horror,” which is the horror of the thing at the end, of the half-brother who isn’t quite human and breaking into the museum to get the sacred/blasphemous book that will release more of those things and this sort of thing. There’s a great moment at the local store when the uncle, who’s helped give birth to these monstrosities, comes in and chats at the local store and says, “I got some people in my family the likes of which you wouldn’t believe. They’re not even human. Indeed they’re better than human and worse.” Yes, and people extrapolate. Marxian, deconstructive thinkers think, “Is Lovecraft really talking about some of the people he met in New York and that he didn’t like very much?” Or is he talking about civilization and decay? Or is it a complete fantasy where it’s just a dream/nightmare where it has no reading beyond the text; it has no reality beyond itself. Who knows?

What we do know is that Lovecraft died penniless in 1937, and yet a publisher and people who admired him, many of the people he’d sent the emails of his era to thousands and thousands of times, all his correspondents, clubbed together to create a publisher called Arkham House who brought him out over the last 20 to 30 years. And then he gradually became a more and more significant figure. Even the great sort of popular novels—I knew somebody who actually printed Stephen King’s It. Six million were printed in Britain alone. Six million! They run the presses at one of the very big printing firms in Britain for 24 hours. It never stopped. Six million. I always think to myself whenever I hear that figure . . . it’s so amazing. It’s come back like a tic. But King has said of Lovecraft, “Lovecraft is the greatest writer of the baroque and highly wrought literary horror fiction in the 20th century,” and, in a way it’s true because he creates his own world, you go into it, you sort of know what you’re going to get.

Other stories are very Poe-esque. There’s another one called “The Outsider” where a man sort of meets himself in the mirror and has dénouement thereby, a self-reflective moment. It’s a very old sort of classic sort of gothic fare. There’s a few extraordinary ones.

One is “The Color Out of Space” where this force comes from without like radiation and infects this farm and they all decay. And there’s great lines in it like, “As Uncle Wilbur sat by the fire . . .” suddenly part of his body falls off. And one of his relatives goes, “Wilbur! What’s happened to your arm?” And he goes, “Aw, shucks, it’s gone and fallen off.” They’re all turning to dust under the radiation, this color that comes from without. The interesting thing about Lovecraft is the monsters are sort of pseudo-scientific. They’re like radiation.

Remember the scientists who created the atomic bomb? They used to chuck bits of the machinery to their children because they knew very little about the concept of radiation. They all died of cancers about ten years later. There’s pictures of them from the Manhattan Project. There’s one famous picture of one of them holding up an inner component from the bomb. He’s holding it on his aunt’s head, thinking, “Gee, look at that. Smile!” You’re on Kodak! She’ll be dead in a couple of years, you know? To write a story like “The Color Out of Space” which deals with the fear of radiation before that was even mentally known is extraordinarily prescient really, isn’t it?

And that’s why I say, in a way, people that like Lovecraft and the tradition that he represents are dreamers, because the old theory that Colin Wilson put in one of his books is a theory that sometimes works, although there’s no scientific basis for it. If you have a face before you photographically and look at the left eye, it’s said that that indicates the inner personality. It’s not scientific, but policemen still use it. It’s very interesting. You look at the right eye and that is allegedly the personality as it’s configured for the world. It’s the mask as they call it in Eastern cultures. It’s that which you wear. The left eye indicates the inner personality. It’s very odd. If you look at many poets there’s an enormous development of the eye. It’s very artistic. It’s just a way of looking or an intuitive way of looking at these things.

But Lovecraft’s eye is not entirely of someone who’s living on this world as mentally he wasn’t. He was a dreamer, a visionary, partly mad, partly sort of glorious, but very much part of our tradition, I think, this capacity for transcendence and a capacity for a sort of Saturnalian and darker element, sort of the notion of that transcendence. I think it’s visionary power in art. I think it’s one of the greatest things we’ve achieved—tragedy is usually the greatest things that we’ve culturally achieved—the Elizabethans, the Greeks. They deal with this sensibility and its power.

And I think that when one sees an advertisement for a mobile phone or one sees some egregious Americana that one doesn’t like the look of, you must always remember these other figures, people like Lovecraft, like Poe, like Eliot, like Lewis—although he was Canadian by birth—often ultra-European figures with their dickie-bow ties and all the rest of it, from the early part of the 20th century, and we understand that there are many Americas and that we feel spiritually closer to the one that they represent than the one that Obama represents.

Thank you very much!

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.